Following a late diagnosis of autism, writer Joanne Limburg learns how the playful techniques of neurophototherapy can help her to reconnect with the unselfconscious and creative parts of herself.

The following text is an extract from a longer essay, published in full as part of the Neurophototherapy publication which you can download for free here.

Neurophototherapy is a practice devised and designed by Sonia Boué for late-diagnosed autistic women and people of marginalised genders. It deploys a blend of methods – photography, collage, performance art – to enable participants to ‘unmask’, re-establishing a connection with that younger, less self-conscious, more playful person, who was not yet weighed down by any sense that their mode of being in the world was ‘wrong’.

There are two main ways to use photography, and they can be combined. One involves connecting with a past self through childhood photographs. Looking at images of one’s younger, unmasked self can help with a process of ‘self-recognition’.1 I experienced such a moment of recognition myself, when I went through old photographs and found this image:

In this picture I am two, or three at the most, and I am with my mother in Golders Hill Park in North London. I am pointing at the deer enclosure, drawing my mother’s attention to the animals, wanting her to come over with me for a closer look. As I looked at the excited little girl and her pointing figure, following her gaze away from her mother and towards the animals, it occurred to me that I am still most comfortable relating to people in this indirect way, signposting: “this is a thing I like”, or “that interests me”, and “I want to share it with you”. That Little Girl Pointing represents a large part of what makes me an artist, a writer, and a teacher.

You can also use photography to unmask to yourself through performance art, by treating it as a kind of play. With this in mind, and inspired by the picture of the Little Girl Pointing, I asked my son to take a series of photos of me doing what has always come naturally:

The idea was to take pictures that showed me acting, as unselfconsciously as I could, as a three-year-old version of me might on receiving a new consignment of Play-Doh. In the purple photograph, for example, I am holding the contents of both purple tubs (one plain, one sparkly) as if they were a bouquet of violets, and taking in that distinctive, vanilla-y smell. In the green and orange pictures, I am squishing the Play-Doh, first with my hand and then with my foot, which felt very much like the kind of action a toddler would be told not to do, and then would do anyway.

Presenting these photographs is a little challenging for me, because they involve a photographically untouched depiction of my 50-something self, with her frown lines, and in the blue picture, her patch of thin hair, left over from a bout of alopecia in my mid-30s. This picture was distressing to see, as I tend to hyperfocus on certain physical imperfections and this is one of them. For this reason, it felt all the more important to leave it in, to emphasize the point that these are pictures of the artist not appearing, but doing. As John Berger pointed out many years ago, acting vs appearing is a gendered binary, and neurophototherapy is a practice designed for women and other people of marginalised genders. Some of the forces driving the pressures to mask throughout our lives come from society’s rules about how women are primarily for looking at, that our value is tied up in how pretty and conventionally attractive we are. Three-year-old me didn’t yet care; perimenopausal me is beginning to see the appeal of caring no longer.

The Importance of Objects

Objects offer another means of linking the artist’s childhood self to their present self. Autistic people often form warm, living connections to objects as well as to people.2 As Boué says, working with long-beloved objects ‘summons the inner child whose best friends often were objects.’3

There was a ‘red’ page in the book. I had no red Play-Doh, so I went to retrieve a red object instead: a round, red enamelled tray with a friendly, colourful flower pattern. The tray had belonged to my grandparents, and would be brought out on Saturday afternoons covered with Tunnock’s teacakes, jam tarts, and Kipling’s French Fancies. Autistic people will understand what I mean when I say that this tray is to me a warmly-remembered senior family member, who has loved me unconditionally. A central principle of Neurophototherapy, as described by the participant Helen Robson, is that of ‘working with safe things’ – ‘working with positive associations, and the insights they bring.’4 Play-Doh, memories of Golders Hill, and the red tray, are all ‘safe things’ for me.

Repairing Memories

Another principle is that nothing made by the participant has to be shared, that this is, above all, an ‘unmasking to oneself’ within one’s own self-created, independent ‘neuroverse’.5

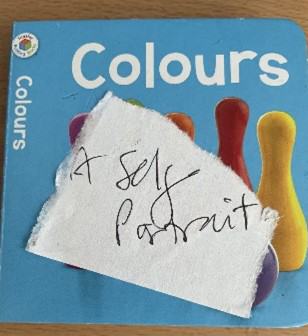

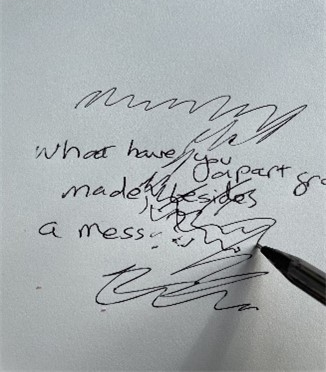

In this safe, self-created, self-directed space, free from any judgemental, external gaze, it may become possible to engage with more ‘difficult’ memories, ‘compartmentalising’ them by ‘being gentle and taking time.’ Boué writes about how one participant ‘… decided to be proactive, reclaim the memory and transform it’ in a ‘”little act of defiance”’.6 For the final image in the Colours book, I used a manipulable, liquid medium – black ink – for my own act of defiance, scrawling in the most raw, messy handwriting the words: ‘What have you made, besides apart from a mess?’. These were words that were spoken to six-year-old me, when a playworker saw my ‘soap sculpture’ during a craft session at a community children’s club. I remember how pleased he was with his quip, and how humiliated I felt.

It was one of a number of experiences through which I came to associate my attempts to produce art with humiliation and shame. Another example: in Sixth Form, I took photography as an extra-curricular activity. Our homework for the first week was to take a series of images. Trying to be clever as usual, I took a series of very close-up images of my brother, a portrait-in-fragments focussing on different parts of his clothed body. In response, I got: ‘What IS this? What am I supposed to DO with this?’ from the class teacher, in a tone of utter disgust. I didn’t go back and never picked my SLR up again.

In scribbling these words down – scribbling them, crossing them out, scribbling around them, photographing and framing them, I experienced the truth of Boué’s assertion that ‘Being intentional about what we work with – to repair negative memories – can also be therapeutic and empowering’.7

So that’s neurophototherapy: therapeutic, empowering and – above all – FUN.

_______

1 Sonia Boué, Neurophototherapy: Playfully Unmasking with Photography and Collage, p.21

2 See, for example, Rebekah C White and Anna Remington, 'Object personification in autism: This paper will be very sad if you don't read it' in Autism Journal, Volume 23 Issue 4. 11 August 2018.

3 Boué, p.54

4 Ibid, p.17

5 Ibid, p.15

6 Ibid, p.17

7 Ibid, p.17

Joanne Limburg is the author of three poetry collections for adults, one for children, three works of non-fiction and one novel. Her most recent book is the collection of linked essays, Letters to my Weird Sisters: On Autism, Feminism and Motherhood.

Other essays and articles have appeared in Aeon, Psyche, Boundless, Poetry Review, The Guardian and the Observer, and she has contributed to essay collections such as The Best Most Awful Job and We've Got This. She lives in Cambridge, where she is a Teaching Associate in Creative Writing at the University of Cambridge Insitute of Continuing Education. Joanne is a trustee of Mainspring Arts, which provides opportunities for neurodivergent artists, and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

Get a free digital copy of the publication by Sonia Boué on the practice of playfully unmasking through photography and collage

Find out more

View some of the work produced by participants of the Neurophototherapy project

ViewBanner image: Sonia Boué, In Among the Ivy, 2023.

Images on page: courtesy of Joanne Limburg.

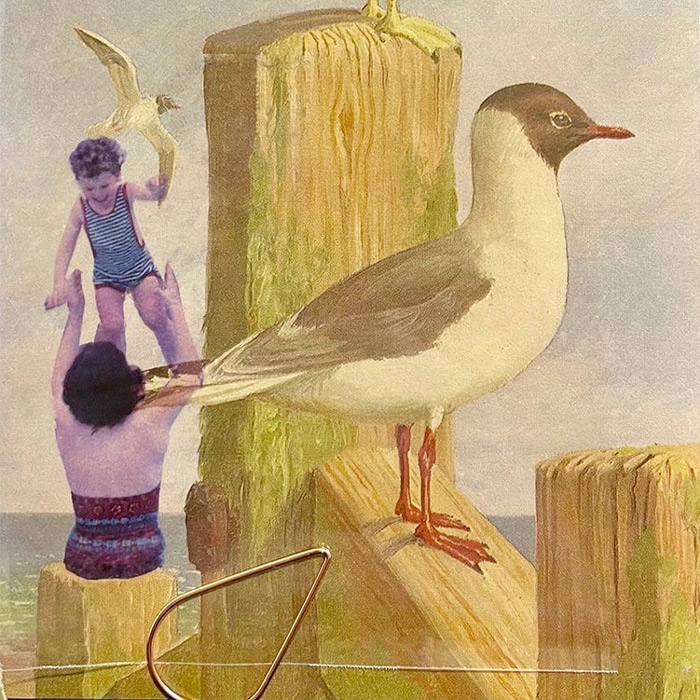

Related content: 1) Sonia Boué, from the series The Artist is Not Present, 2023. 2) Lucy Barker, analogue collage made as part of the Neurophototherapy Project, 2023.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.