In 2007, Swiss-Haitian artist Sasha Huber joined the committee of Demounting Louis Agassiz, a campaign seeking to renegotiate the legacy of the lauded scientist - who was also a racist. Agassiz commissioned a series of photographs of enslaved people from the Congo to 'scientifically prove' the inferiority of the Black race. Huber has created compelling decolonial works based on these portraits, redressing such issues.

In this conversation, Bindi Vora speaks with Huber on

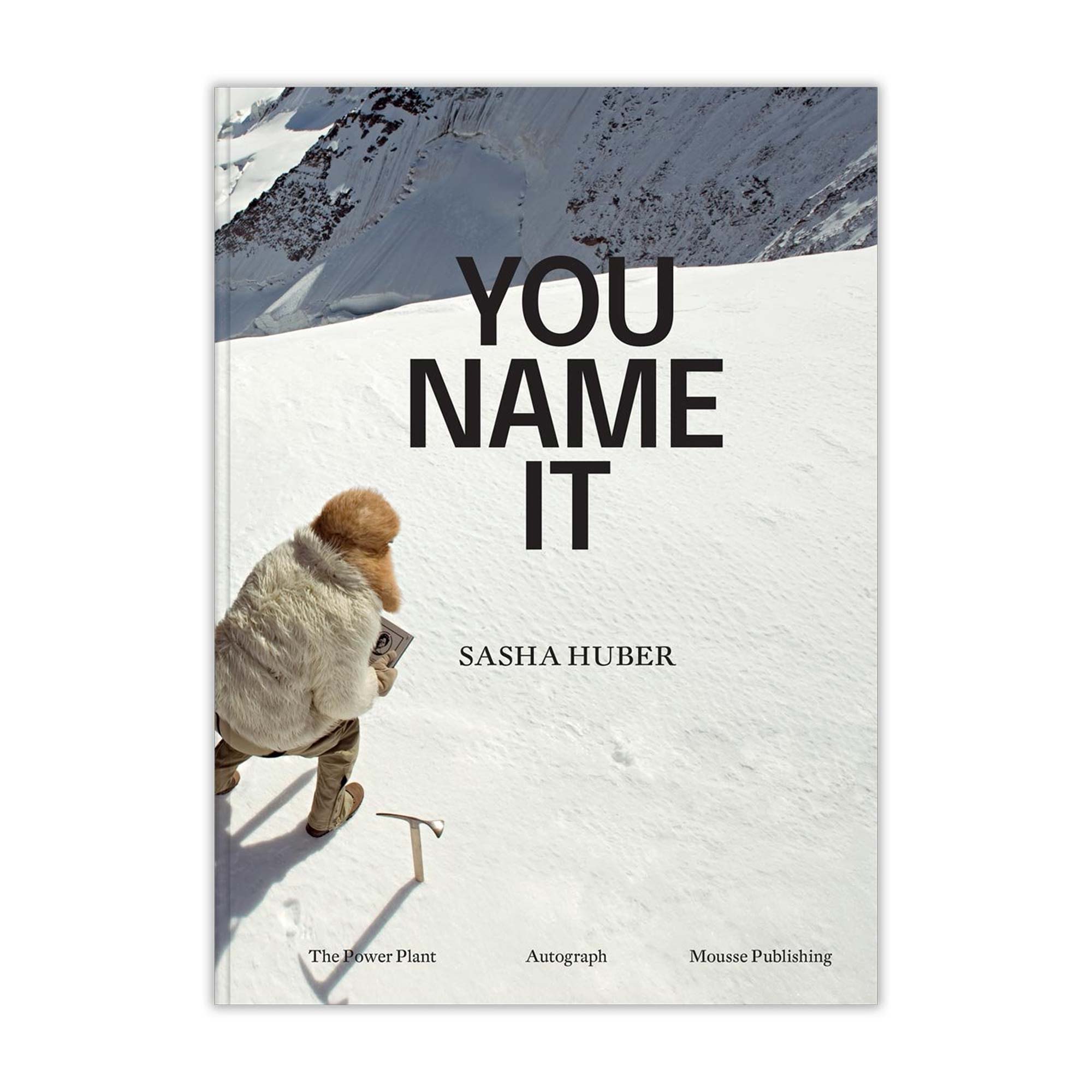

the occasion of her first UK solo exhibition, YOU NAME IT,

on show at Autograph until 25 March 2023, curated by Vora, Renée

Mussai and Mark Sealy. They discuss the work of healing

colonial wounds and how we might resist violent histories

and [in]visibility to achieve liberation.

Bindi Vora (BV): It is a huge pleasure to be in dialogue with

you, Sasha, having spent so much time with your work

and, of course, the privilege of co-curating your solo

exhibition, YOU NAME IT, at Autograph. Your practice

is deeply rooted in visual activism and particularly

tethered to the Demounting Louis Agassiz campaign,

which is where I want to begin. Can you tell us about the

campaign and why you became involved?

Sasha Huber (SH): Thank you, Bindi. My engagement with

the campaign started when I read the 2006 book

Reise in Schwarz-Weiss: Schweizer Ortstermine in

Sachen Sklaverei by the Swiss historian and political

activist Hans Fässler. His book was about Switzerland’s

participation in the transatlantic slave trade; its banks

and businesses profited from the plantation system in

the Caribbean. This colonial history was never part of

Switzerland’s school curriculum when I was studying.

I decided to contact the author, Fässler, to continue

the conversation and introduce him to the decolonial

artworks I had been creating. The 2007 activities

commemorating the 200th birthday of Louis Agassiz

celebrated his work as an influential naturalist and

glaciologist but made no mention of the fact that he was one of the most influential racists of the 19th century,

nor the fact that he was an ideological forerunner of

apartheid. This oversight prompted Fässler to initiate

the Demounting Louis Agassiz campaign, which centres

around a proposal to rename Agassizhorn, a mountain

of the Bernese Alps in Switzerland – one of more than 80

landmarks named in Agassiz’s honour. The new name he

proposed was ‘Rentyhorn’ in honour of Renty Taylor, an

enslaved man originally from the Congo who, alongside

six other enslaved persons, was forcibly photographed

on a South Carolina plantation. These photographs,

often referred to as the ‘slave daguerreotype series’, are

the first-known photographs of enslaved people and

were commissioned by Agassiz to ‘scientifically’ prove

the inferiority of the Black race. Fässler invited me to

join the transatlantic committee alongside other activists,

historians, journalists, artists and politicians.

BV: Do you think your involvement in the Demounting Louis Agassiz committee, as well your cultural experience, being both Swiss and Haitian, has informed the way you see the world?

SH: My dual heritage gave me a lot to think about and

it also became the starting point and inspiration for

my work. I was concerned about family and historical

events, and I was able to articulate this through my work

which helped me to make sense of myself and the world

we live in. Interestingly, after joining the Demounting

Louis Agassiz committee, I learned that history can be

renegotiated and that I could contribute to this slow

process with my art. Looking back, I see that as a key

moment for me, which made me step outside of the studio

and become more active, not just with my work but also

in my desire to collaborate with others.

I soon felt that I wanted to use my energy to create portraits of our ancestors and people who had been silenced throughout history, who were – or still are – negatively impacted by colonialism; works that commemorate and memorialise. This was a turning point for me and henceforth my shooting of staples has sought to enact a stitching of colonial wounds. It was a way for me to make visible and tend to those wounds – I started to call my works ‘pain-things’."

BV: Tailoring Freedom (2021–2022) forms part of this ongoing advocacy work, addressing the disputed legacy of Louis Agassiz and the aforementioned daguerreotype images of seven enslaved individuals, including Renty and his daughter, Delia. The images were intended to give credence to Agassiz’s white supremacist beliefs and ‘prove’ the inferiority of Black people. All seven of the figures are depicted unclothed on the Edgehill Plantation in South Carolina, USA. The original daguerreotypes (now housed at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University) have been the subject of many ongoing debates around authorship, ownership and decolonial practices, especially as Tamara K Lanier – a descendent of Renty and Delia – has sought to repatriate the original photographs. Why was it important to you to create portraits of Renty and Delia to

begin this work?

SH: I only found out about the daguerreotypes when I joined the Demounting Louis Agassiz campaign in 2007. When I started to work on my first reparative intervention as part of the campaign group’s renaming efforts, I went to Agassizhorn to rename the peak – physically and literally – to Rentyhorn. I carried a metal plaque featuring an illustration of Renty, alongside a short description,

all the way to the peak and documented the action. In addition, I made a petition website – rentyhorn.ch – and sent a letter of request to the mayors of the communes sharing the mountain in Grindelwald, Guttannen, Fieschertal and the Unesco World Heritage Committee.

In 2012, we received an email from Tamara K Lanier after her daughters discovered my petition. They came to an exhibition opening in Grindelwald held near the mountain to raise awareness of Agassiz’s racist history where she spoke about Renty. She gave Renty his dignity back – emphasising his importance amongst their family and sharing with everyone what kind of a person he was: he could read, he taught his children, he was spiritual, and much more. It was moving to get to know her and we have stayed in touch ever since. When Tamara filed a lawsuit against Harvard University in 2019, she wanted

to retrieve her ancestors’ photographs from this powerful institution which, according to her lawyers, was still owning and ‘selling’ her ancestors through the reproduction of their portraits. As I understand, this action follows in the steps of enslaved people who pursued ‘freedom lawsuits’ to petition for their emancipation. Tamara’s case was dismissed by the Superior Court in March 2021 and by the Massachusetts Supreme Court in October 2022. It was not a surprise, but still a disappointment. However, the court has permitted Tamara to pursue an ‘emotional distress claim’ against Harvard if she wishes. It is bittersweet news, and I don’t know if she will proceed. I believe that her attorneys will stay committed to her and that they will continue to support her despite not being able to free Renty and Delia as she had hoped to.

BV: We have touched on some of the experiences that

you draw upon when making work, but I want to delve

into the role of the archive within your research. You often

turn towards archival imagery as a base material when

making portraits of significant historical figures like we

see in your series The Firsts. How do you settle on an

image or a figure to work with?

SH: My interest in photographic archives started way

back. At first, I was drawn to my family’s archive.

I especially admired the black-and-white portraits of

my mother, Monique Huber-Remponeau, and her sister, the early generation Black fashion model Jany Tomba, and my artist grandfather, Georges Remponeau, in New York, where the family emigrated to in the mid1960s. Whenever I got a chance to look at the albumen prints, and boxes filled with photographs, I wanted to see and hear their stories. My mother would tell me about her apprenticeship at the Abraham photo studio during the mid-1950s in Port-au-Prince where she learned the skill of retouching portraits directly onto the ambrotype

glass-plate negatives.

In 2004, I began the series Shooting Back – Reflections on Haitian Roots, criticising those individuals who contributed to the historical and social conditions in Haiti, from the 15th to 20th century. I began with a portrait of Christopher Columbus and went on to create portraits of Françoise ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier and his son, Jean-Claude ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier. This was the first time I was making

portraits entirely rendered using metal staples ‘shot’ onto wooden boards. I wanted to use the staple gun to metaphorically but also literally ‘shoot back’ at figures like Columbus. At the time it gave me a sense of agency and the ability to react to an unjust history. Each staple represented a life lost to the transatlantic trade as well as those adversely affected by the autocratic regime in Haiti.

I soon felt that I wanted to use my energy to create portraits of our ancestors and people who had been silenced throughout history, who were – or still are – negatively impacted by colonialism; works that

commemorate and memorialise. This was a turning point for me and henceforth my shooting of staples has sought to enact a stitching of colonial wounds. It was a way for me to make visible and tend to those wounds – I started to call my works ‘pain-things’. Since then, I have made several portraiture series, such as Shooting Stars (2014–ongoing) and, as you mention, The Firsts (2017–ongoing).

BV: These works raise crucial questions about the ethics and politics of the gaze and how we might be able to look with sensitivity at such images. As we were conceptualising the exhibition for Autograph, it was important from our perspective to draw focus onto the Tailoring Freedom portraits, situating the works in a contemplative space to further emphasise the need for reflection. In these new portraits you have merged multiple facets of your practice to create these works, using photography and your signature staple-gun method. You have managed to depict violence without reproducing violence and each portrait refuses the role of the objective camera. Can you speak about why this body of work has been significant in your practice and why the merging of these two mediums was important?

SH: When I first started the Rentyhorn project in 2008,

I made an ink drawing of Renty dressed in traditional Congolese clothing rather than stripped bare, as the daguerreotypes depict. I recently revisited these sketches, having forgotten about them. Seeing them again, I realised that subconsciously I had already imagined freedom for them through my critical fabulation. Tailoring Freedom was conceptualised before knowing the

outcome of the lawsuit. Now, after Tamara’s unsuccessful efforts to gain her ancestors’ freedom through repatriating the original photographs, I returned to this methodology and these initial sketches. Having spoken with Tamara about the case on several occasions, I decided that the final portraits of Renty and Delia should be gifted to her. I printed the photographs of Renty and

Delia onto wood, mounting them as a diptych for them to stay together. It was the first time that I married stapling with photography as usually I create the entire image from staples. I came to think, yet again, how fine clothing can be a symbol for freedom, especially because it was something enslaved people could never have. When I started to research what kind of clothing I could ‘tailor’ for them, I started to look at images of the abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, both of whom were able to self-emancipate in their lifetime. Douglass’ status as the most photographed person in the USA during the 19th century was also an important aspect. When I showed the work to Tamara, she said that I had successfully ‘taken them out of their circumstance’ and

‘given them their dignity and humanity back’.

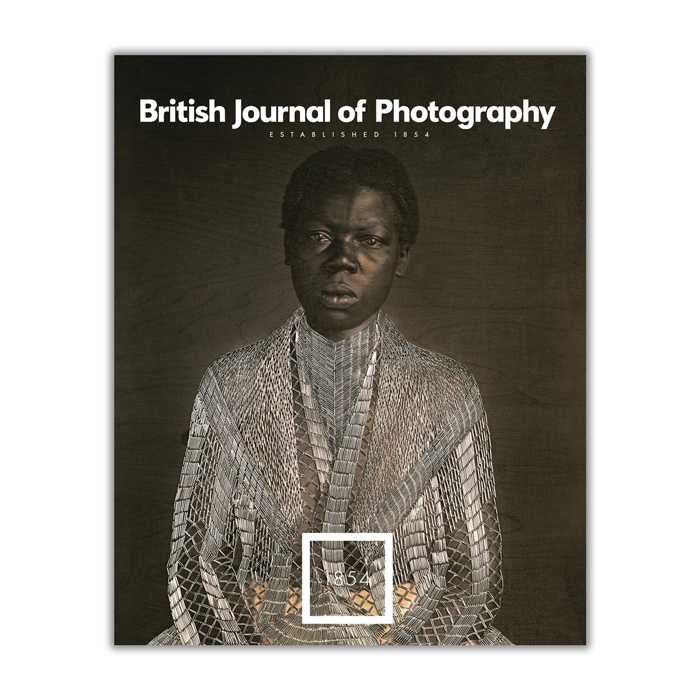

BV: These monochromatic works bring to life the haunting presences of the seven enslaved individuals and draw us into their gaze. In the two portraits depicting Jack and his daughter Drana [which appear on the cover of Issue 7911 of the British Journal of Photography] , you made a conscious decision to clothe each of them as a gesture of reparation and dignity. Would you be able to share some insights into the inspirations behind the glimmering attire that has been so intricately and very beautifully woven using your signature airstaple-gun method?

SH: Delia and Renty are lucky that their descendants know about them and that they fight for their freedom. This is not the case for Jack and Drana, Alfred, Fassena and Jem. We don’t know much about them, or if they have descendants. I felt it was important to

collectively remember all seven of the figures from the daguerreotypes because they were a community. They knew each other. Now within this complete series they are all together, side by side. I’ve depicted Drana in a dress inspired by Sojourner Truth whose liberation history is remarkable; she went to court back in 1828

to fight for the recovery of her son from slavery and was the first Black woman to win such a case against a white man. During the making of this work, bell hooks’ book Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (1981) was something I returned to. The title, Ain’t I a Woman, is taken from a speech given by Sojourner Truth

– one of history’s most important speeches on abolition and women’s rights ever given. It gave me a deeper understanding of the precarity of Black womanhood during slavery, the racism and sexism women were

exposed to, and how this history affects our present time.

BV: What does it mean for you to have this collection of works displayed at Autograph, given our history of redressing archives and of bringing often unheard narratives to light?

SH: I have been acquainted with Autograph’s work since 2010, so to see my exhibition come to life in the gallery space feels like a dream, like my work has come full circle in a way. Tailoring Freedom resonates especially strongly with Autograph’s philosophy, I think. I’m incredibly grateful that I have been able to develop this series and bring together so many years of work and advocacy to the public to understand the embedded histories alongside a dedicated book, YOU NAME IT. It means a lot to me and I’m grateful to everybody who has supported me in this ongoing journey.

11 Nov 2022 - 25 Mar 2023

Free exhibition at Autograph's gallery in London

Featuring Sasha Huber's work Tailoring Freedom alongside new works from Kalpesh Lathigra, Samuel Fosso and Aneesa Dawoojee amongst others

Buy it from the BJP shop

A new, comprehensive publication focusing on the artwork and activism of Sasha Huber

Buy it hereBanner image: Cover spread of Issue 7911 of the British Journal of Photography, The Portrait Issue, featuring Sasha Huber, Tailoring Freedom – Jack and Drana, 2022. Metal staples on photograph on wood, 97 x 69 cm. Courtesy the artist. Commissioned by The Power Plant, Toronto; Autograph, London; Turku Art Museum, Finland; and Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2022. Original images courtesy the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (Jack, 35-5-10/53043; Drana, 35-5-10/53041).

Images on page: 1) Sasha Huber, Tilo Frey from the series The Firsts, 2021. Courtesy of Autograph, London. 2) Sasha Huber, Tailoring Freedom – Renty and Delia, 2021. Courtesy Tamara Lanier and the artist. Commissioned by The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto; Autograph, London; Turku Art Museum, Finland; and Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam. Original photographs: Renty 35-5-10/53037; Delia 35-5-10/53040, courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. 3) Sasha Huber, Tailoring Freedom – Jem, 2022. Metal staples and photograph on wood, 49 × 69 cm. Original images courtesy the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (35-5-10/53046). © the artist. Courtesy of / commissioned by The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto; Autograph, London; Turku Art Museum, Finland; and Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam. 4) Sasha Huber, Tailoring Freedom – Fassena, 2022. Metal staples and photograph on wood, 49 × 69 cm. Original images courtesy the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (35-5-10/53048). © the artist. Courtesy of / commissioned by The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto; Autograph, London; Turku Art Museum, Finland; and Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam. 5) Sasha Huber, Tailoring Freedom – Alfred, 2022. Metal staples and photograph on wood, 49 × 69 cm. Original images courtesy the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (35-5-10/53049). © the artist. Courtesy of / commissioned by The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto; Autograph, London; Turku Art Museum, Finland; and Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam 6) Sasha Huber, Somatological Triptych of Sasha Huber VII, Agassiz Island, Lake Huron, Ontario, Canada, from the series Agassiz: The Mixed Traces, 2022. Commissioned photography by Daniel Ehrenworth. 7) Sasha Huber, Somatological Triptych of Sasha Huber V, Agassiz Lake, Quebec, Canada, from the series Agassiz: The Mixed Traces, 2017. Commissioned photography by Jake Hanna.

Other images: 1) Sasha Huber, Agassiz Down Under [detail], 2015. Courtesy the artist. 2) Sasha Huber: YOU NAME IT exhibition at Autograph. 11 November 2022 - 25 March 2023. Curated by Renée Mussai, Mark Sealy and Bindi Vora. Photograph by Kate Elliot. 3) Sasha Huber, Khadija Saye - You Are Missed [detail], 2021-22. Metal staples on fire burned wood; 104.5 x 73.5 cm © the artist. Courtesy of / commissioned by Autograph, 2021. Supported by Art Fund. 4) Sasha Huber, Tailoring Freedom – Renty, 2021. Courtesy Tamara Lanier and the artist. Commissioned by The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto; Autograph, London; Turku Art Museum, Finland; and Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam. Original photograph: Renty 35-5-10/53037, courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.