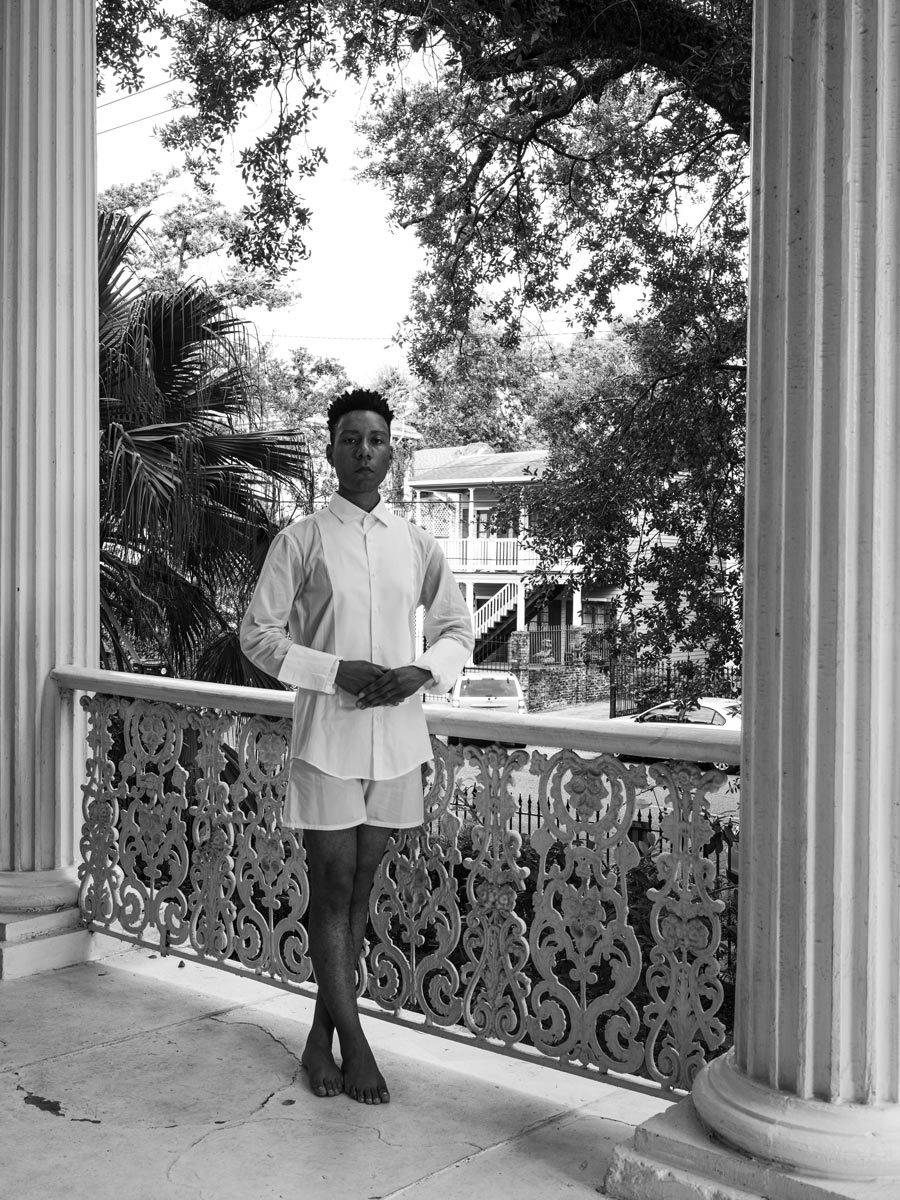

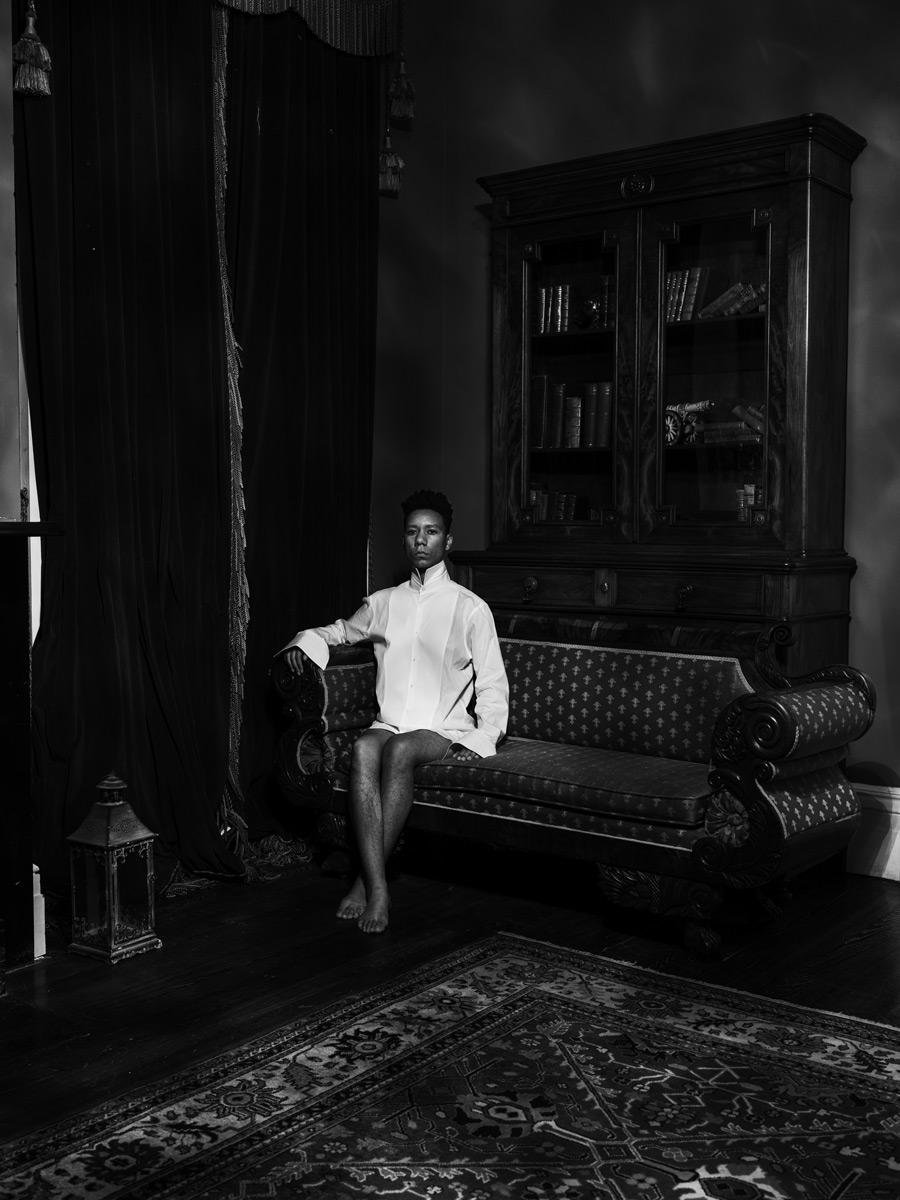

Focused on the intricate dynamics of visibility and authority, Talking Back to Power proposes a reclamation of black visibility. C. Rose Smith’s evocative black and white self-portraits revolve around the white cotton shirt, staged at locations affiliated with the wealth generated from cotton plantations in the Southern United States of America.

During the 19th century, cotton was one of the most lucrative global commodities. Built on the forced labour of millions of enslaved Africans, plantation complexes that grew, cultivated and sold this crop formed the basis of monumental economic advancement and progress.

Throughout her photographs, Smith fashions a crisp white button-up shirt, a potent emblem of both exploitation and respectability. She poses in opulently decorated antebellum homes in Tennessee, South Carolina and Louisiana, by-products of the wealth amassed by the owners of cotton plantations. Entrenched throughout these buildings is the lingering spectre of the magnitude of violence and anguish that is inextricably linked to chattel slavery. Despite many undergoing meticulous restorations and now serving as tourist destinations, these buildings bear witness to the enduring legacy of human suffering.

Emulating the formal compositions of 19th century oil paintings, Smith’s portraits powerfully reflect on the black body as a former commodity. Her unwavering gaze and confronting presence demands visibility as an act of resistance. In the artist’s own words: “it is unexplainable and almost unimaginable to take up the freedom of expression as a maker of images…there is an unsettling consolation in confronting, addressing and contesting structures that have and continue to exist as archives of anti-blackness."

Belmont Mansion is a stark reminder of the history of forced labour in the American South. Built by enslaved peoples and European immigrants in 1850 for Isaac Franklin and Adelcia Acklen it was the largest home in the state of Tennessee prior to the American Civil War.

Isaac Franklin and his business partner, John Armfield, were deeply involved in the slave trade. Their operations extended across several Southern States, and they became the most prolific traffickers of enslaved people: profiting from the sale and separation of families. Following Franklin’s death, Adelcia Acklen continued to benefit from the wealth amassed from exploitation.

St. Helena’s Parish in Port Royal holds a

prominent place in the history of cotton

cultivation, particularly for its production

of sea island cotton, one

of the rarest and most expensive types

of cotton to be produced. In its early

years, the production of sea island cotton

increased from 4.5 kilograms in 1790, to

3855 tonnes by 1801. This exponential

growth was fuelled by high demand for

luxury cotton in England.

The remains of

the Chapel depicted in this photograph

was built in 1740 and bears witness to its

history. Constructed from oyster shells and

limestone by enslaved people labouring

on plantations in the area. During the

peak of cotton cultivation in St. Helena’s

Parish, 80% of the island’s population was

enslaved. This stark demographic reality

underscores the deep connections between

cotton production, slavery, and the

economic prosperity of the region.

"There is a humility in sitting as an act of rest in starched white cotton garments, envisioning my ancestors labouring in endless fields…knowing who I belong to, a race of people who are the true and living architects of this nation."

– C. Rose Smith

The Harris-Maginnis House stands as a testament to the Antebellum era in America, a period marked by both opulence and violence. Built in 1857 in the heart of New Orleans, this mansion was a symbol of the wealth and success of the Maginnis family, who were prominent figures in the cotton industry.

The Maginnis Cotton Mill, one of the largest in the Southern United States, produced a staggering 19 million

metres of cotton annually at its peak. The

prosperity of the mill was built on the

labour of enslaved people. They endured

gruelling hours in hazardous conditions:

many suffered from debilitating lung

diseases due to exposure to cotton dust,

while others fell victim to tragic accidents

whilst using the machinery, resulting in

severe injuries or even death.

New Orleans

was at the centre for the buying and selling

of enslaved people, profiting exponentially

of forced labour; the city became a crucial

link in the cotton triangle that connected

the American South to Britain.

The Nottoway Plantation house was built by enslaved labourers for John Hampden Randolph in 1859. Facing the Mississippi River, it is the largest plantation house still standing in the Southern United States. The handmade bricks used to build the 4,900m² mansion were baked in kilns by enslaved workers.

John Hampden Randolph was from one of the wealthiest and most powerful families in 18th-century Virginia. Having grown up on his father’s plantation in Georgia, Randolph eventually owned his own plantation in Louisiana. Through the wealth he amassed from enslaved labour and the cultivation of cotton and sugar, he acquired acres of land in the states of Iowa, Minnesota, and Texas. Nottoway Plantation is now a resort destination and tourist attraction.

Joseph Aiken was a prominent cotton merchant based in Charleston, South Carolina. The city was a hub for the cotton industry, which was one of the primary economic drivers of the Southern economy

before the American Civil War (1861-1865). In addition to trading in cotton, Aiken had a military career, serving as a Lieutenant in

the Confederate Army. Formed by Southern States, the Confederate Army fought to preserve the rights of the institution of slavery.

By 1860 the enslaved population in South Carolina was 402,000. The broader historical context of the American South during the 19th century meant traders, like Aiken, profited immensely from the

exploitation and suffering endured by enslaved people, in order to produce lucrative crops like cotton.

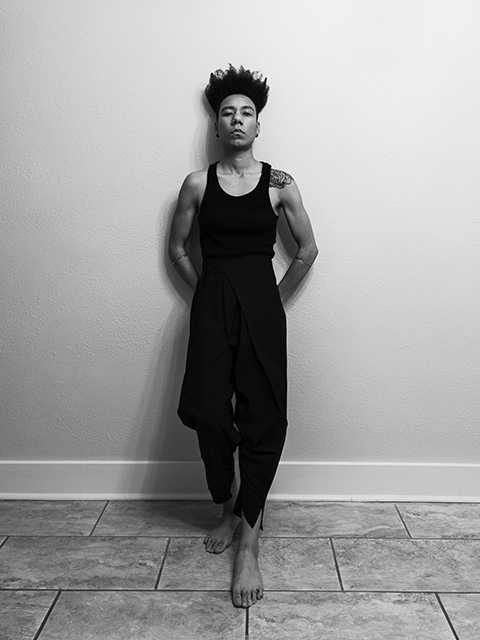

C. Rose Smith (born 1995), is a visual artist examining the role of photography in constructing the layers of identity and individuality.

Using fashion, site-specificity and elements gleaned from studio-portraiture, her photographs engender a subversive performance that gestures a critique of social norms. Her work has been exhibited in group exhibitions in the U.S. and Europe, and is held in private collections. Smith earned an MFA in Photography and Related Media at the Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, NY and earned a BFA in Photography from Savannah College of Art and Design in Atlanta, GA. She is based in Memphis, TN.

All images by C. Rose Smith, courtesy the artist. Banner: Untitled no. 55, Nottoway Plantation, White Castle, Louisiana [detail].

Exhibition install: C. Rose Smith: Talking Back to Power exhibition at Autograph. 13 June - 12 October 2024. Curated by Bindi Vora. Photograph by Kate Elliott.

About the artist: Courtesy of C.Rose Smith (2024).

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.