Autograph’s current exhibition The Studio – Staging Desire features never-before-seen works by Rotimi Fani-Kayode, shot in his home studio - a space which transcended into a sanctuary for visualising Black queer self-expression.

Using the language of jazz, photography and improvisation, writer Ishy Pryce-Parchment provides a personal reflection prompted by the exhibition, exploring the parallels between his own practice and experiences, and that of Fani-Kayode.

In a series of untitled photographs, a Black male model stands nude on a small black table, concealing his intimate area. Against a makeshift grey backdrop, he twists and writhes; in three of the four frames, he obscures his face with a hand or an arm, his movements suggesting a pained intensity. His poses, resisting the statuesque, carry a sense of melodrama – perhaps revealing an internal conflict. The series enacts a duality through performance, highlighting the struggle to disrupt fixed readings of the body while gesturing towards new possibilities for reimagining the Black, queer body’s being-in-the-world. This staged, performative quality recurs throughout the exhibition and in Fani-Kayode’s photography more generally, and offers new possibilities for self-representation.

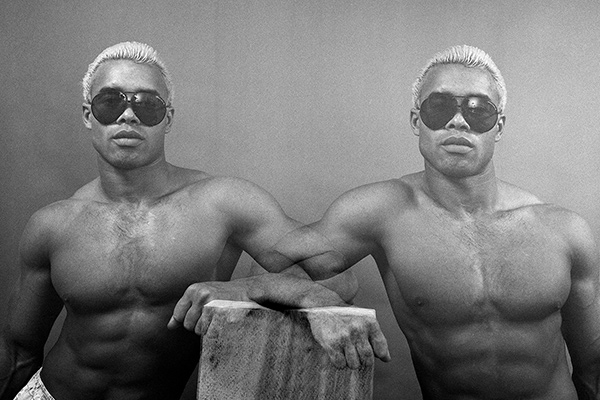

The idea of the studio as a performative site, or a liberatory space, is not a new one. The studio is often understood as more than just a physical space; it is a laboratory for experimentation, a site where identities and bodies are rehearsed into being. It’s where artists navigate process and hone technique. Central to Fani-Kayode’s practice was his incorporation of techniques of ecstasy, a Yoruba practice of possession through which the body is activated in ritualistic or ecstatic ways. For Fani-Kayode, this is also a method for channeling and performing multiple identities, experiences and histories.

This performative dimension is what first made me think about the concept of woodshedding, a term I borrow from jazz which describes the rigorous, private act of rehearsing technique and improvisation for the purpose of self-refinement. I’m not the first to make this connection; as Ian Bourland notes in his reading of Fani-Kayode’s works, "the act of photographing itself becomes activated, rhythmic – like improvisation within a jam session."¹ As a form of woodshedding, Fani-Kayode’s images serve not so much as a space to think about identity, but to question the ability of the body to retain its position as a coherent signifier of experience or identity. The studio, like the woodshed for the musician, is a space where the performative is more than a means of self-expression, it's a profound exploration of the boundaries between personal and collective experience.

While in London, Fani-Kayode worked from a studio in his Brixton flat alongside his partner and collaborator Alex Hirst. The studio was his stage, his woodshed, his ritual space, described by Bourland as "an ecosystem in which to enact and picture ruptured boundaries – sexual, ontological, geographic – and to taunt (or come to grips with) mortality."² It was a space filled by friends, collaborators and models, and imbued with an erotic mysticism. As friend and fellow photographer Robert Taylor commented, it was "a strange little world that was only properly apparent when the lights were cut and ‘normal’ life resumed."³ As a space of play and improvisation, Fani-Kayode’s studio was an ideal site from which to resist the violence of Western visual regimes, which often erase Black multiplicity and reduce Blackness to either abjection or spectacle. Here, the studio allowed for the rehearsal and performance of alternative ways of being – ways that defied these restrictive visual canons. As Taylor confirms, "typical portraiture was the furthest thing from any of our minds."⁴

During my graduate studies at New York University I was given a studio workspace in the Brooklyn Army Terminal, a repurposed warehouse complex. Even though it was a shared studio, I encountered only one other student over the course of my residency. What I thought would be an experience of sharing space and work, of helping out studio mates with whatever project they had going on, turned into a largely solitary experience. This was the first time I had a dedicated studio space, and maybe my first sustained attempt to think critically about process, technique and referentiality.

As a former jazz musician, I hadn’t realised I had been woodshedding long before I had a name for it. When I was learning to play jazz on the tenor saxophone, much of my rehearsal time was spent familiarising myself with different scales and modes. I was taught that to improvise is not to play without rules, but to push against them, to explore the tension between form and disruption.

This tension is what draws me, again and again, to Fani-Kayode’s photographs – the way they syncretise traditional Yoruba iconography with the style of western Old Masters. Each image captures bodies, not as stable or knowable subjects, but as sites of encounter and multiplicity. His models perform and each of his frames rehearse identity, desire and exile. The work does not seek to define, but to unmake, troubling the very categories through which Blackness, queerness and selfhood are often read. His images, in their performativity, engage in a deconstruction of what Professor Stuart Hall theorised as ‘the essential Black subject.’

As an artist navigating multiple identities – West African, Black, migrant, gay, child of exile – Fani-Kayode's visual language anticipated many of the theoretical frameworks that would emerge in the late 1980s, from Judith Butler’s theory of gender and performativity to José Esteban Muñoz’s concept of queer disidentifications. His images actively destabilise the notion of a singular, essential Black self, through using the studio not simply as a site to explore identity, but to interrogate the very capacity of the body to function as a stable signifier of experience and selfhood.

Like Fani-Kayode, I am interested in the meanings of erotic investment, where the Black male nude (as it is represented in visual culture) produces ‘erotic value’ for Whiteness – a subject which Fani-Kayode appears to critique in his work White Flowers ('Olympe'). But more than that, I am interested in how photography can expose and trouble these dynamics. I want to explore if, and how, the subject can be renegotiated in private space and how the act of woodshedding in the studio might offer a model for the transformative and utopian impulses of private performance.

In my final semester at New York University, I took The Black Body and The Lens, a course taught by visual artist Deborah Willis. It was in this class – while studying the histories of Black representation in photography, print, video, and film – that I first encountered Fani-Kayode’s work. His photographs spoke to me, not only through their aesthetic intensity but through their deeply personal engagement with the complexities of exile, queerness and Blackness. For my final project, titled To the Woodshed, I found myself thinking about Fani-Kayode’s work, about the idea of performance, and about the parallels between his experiences and my own. With grandparents who migrated from the Caribbean and as a Black, queer photographer who also spent time in New York for graduate study, I recognised something familiar in Fani-Kayode’s drive to negotiate identity via the camera.

To the Woodshed was animated by my own experiences of not comfortably fitting inside the boxes that people assume I sit in, or want to put me in. It was about the overdetermined signification of the Black body in Western visual imagination, always read in ways that run counter to any kind of self-identity. To ask: do I only know myself through these negotiations between visibility and invisibility? From the outside in, so to speak? Or was there a way of working through the performative, using my own body – it’s gestures and impulses – to reveal, in John Akomfrah’s words, "hidden worlds" and "new visions" away from the excess of associations, interpretations and projections on and of the Black body within Western visual culture.⁵ One of my core questions was about what photography had to do with what historian and writer Saidiya Hartman calls "the import of the performative", and how the performative exposes needs and desires that radically call into question the order of power and its production of cultural intelligibility.⁶

Taking the concept of woodshedding as a point of departure, I explored if and how the subject can be re-negotiated in private space and thought through the transformative and utopian impulses of private performance. I began to see the studio as a backdrop for rehearsing selfhood – a place where performances emerge not from external expectation but from within. It became a space to continuously reshape my interior life on my own terms. Following this realisation, I created images that captured this process: alone in the studio, I was a soloist in private space – improvising, testing, revising, dancing, unmaking.

I was shedding.

_______

¹ Ian Bourland, Bloodflowers: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Photography and the 1980s (2019), p.45

² Ibid, p.242

³ Ibid, p.243

⁴ Ibid, p.243

⁵John Akomfrah, On the Borderline (1991), p.188

⁶ Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection (1997), p.56

Ishy is an artist and recent graduate of the Interdisciplinary Studies programme at New York University. They are interested in writing in and about the archives, photography, performance and the body. His debut Or was it that i wanted it to be as quiet as that? is available through Bottlecap Press. Follow them on Instagram at @ishystfu.

31 Oct 2024 - 22 Mar 2025

Free exhibition

This text is a result of our Call for Writing on The Liberatory Space of the Photography Studio.

Banner image: Rotimi Fani-Kayode: The Studio - Staging Desire exhibition at Autograph. 31 October 2024 - 22 March 2025. Curated by Mark Sealy. Photograph by Kate Elliott.

Images on page: 1-4) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled, c. 1988-1989. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode and courtesy Autograph, London. 5) Ishy Pryce-Parchment, The process of becoming intimate (After Bill T. Jones), 2023. © and courtesy Ishy Pryce-Parchment. 6-8) Ishy Pryce-Parchment, Erotics of Fugitivity (Triptych), 2023. © and courtesy Ishy Pryce-Parchment. 9) Ishy Pryce-Parchment, Untitled, 2023. © and courtesy Ishy Pryce-Parchment. 10) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, White Flowers ('Olympe'), 1987. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode and courtesy Autograph, London.

About the author: Image courtesy of Ishy Pryce-Parchment.

Visit the exhibition: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled [detail], 1988. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.