The daughter of political refugees who were forced to flee Iran, Sheida Soleimani’s work is deeply influenced by personal experiences of exile, persecution and migration. Below, Autograph’s Senior Curator, Bindi Vora, discusses Flyways, the artist’s ongoing series of narrative tableaux exploring issues of migratory labour and invisibilised care work. A selection of works from the series feature in Autograph’s current exhibition I Still Dream of Lost Vocabularies, a group exhibition examining political dissent and erasure through the idea of collage.

This text was first published in the catalogue of the 2025 MAST Photography Grant on Industry and Work, and is republished here courtesy of Fondazione MAST, Bologna.

A few summers ago, during the ebb and flow of the pandemic, my partner and I sat in our garden in London, savouring the warmth under a red, auburn sunshade. After months of work restoring the garden into our private oasis, we cherished these fleeting moments at the end of each day, grasping onto those permitted durations of air and light. Overhead a passenger plane roared, its engine slicing through the quiet with a kind of haste and urgency that felt foreign in those times. In stark contrast, as we returned our gaze, a small blackbird flitted through the trees, gently gliding before perching on my partner’s shoulder. Its head twitched to take in the world around it, its small feathers glinting softly in the sunlight, before it joined the tailwind of the plane.

Years later, I'm reminded of this disparate memory, stirred by the Iranian American artist Sheida Soleimani’s new body of work, Flyways (2024). In a complex constellation of traumatic stories, layered tableaux and meticulous research, Flyways is staged as a powerful counter-narrative to migratory labour, invisibilised care work and the precarity of communication. The narrative unfolds through two concurrent threads: the unheard or in some instances censored experiences of women in the Women, Life, Freedom movement¹ in Iran, and the migratory birds wounded as a result of manmade structures. Soleimani examines the cyclical reality of how infrastructures of power, architecture and systems of hierarchy are designed to wound and kill in myriad ways. But how do we untangle this narrative to decipher the codes embedded in this work? How do we recognise the inextricable links tying the labour and care of wildlife to structures created by those in power – and their detrimental effects on human life as well?

But a caged bird stands on the grave of dreams

his shadow shouts on a nightmare scream

his wings are clipped and his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

– Maya Angelou²

Soleimani has become widely recognised for her politically charged works exploring themes of human rights, sociopolitical geopolitics and the complexities of identity. Her work is deeply informed by her family’s experiences of exile and persecution in Iran alongside her role as a caregiver at her wildlife rehabilitation clinic Congress of the Birds.³ Soleimani’s parents were political activists in the late 1970s and 80s in Iran. Her mother, a nurse, and her father, a doctor, were part of the dissident movements alongside many young Iranians before the revolution. They often worked at the forefront of life and death, providing care in guerrilla field hospitals to those in precarious, life-threatening situations whilst continuing to speak out against the regime.

The repercussions of going against an autocratic ruler were severe: her mother spent a year in solitary confinement, where she was tortured, harassed and psychologically abused in an attempt to extract information about her father’s whereabouts. After the revolution, they were forced to flee as political refugees, her father in 1984 and her mother in 1986, eventually coming to the United States of America, but the traumatic effects of this time can’t even be fathomed.

The throat-cinching words from Maya Angelou’s poem Caged Bird reverberate on my skin; her nuanced way of weaving ideas of freedom, confinement and hope into the texture of the language are palpable. The inherent symbolism serves as a reminder of those who face systemic injustices and oppressive regimes but also speaks to the resilience and resistance needed to fight back - voices like Soleimani’s mother’s and women like her who cannot be silenced. Her Maman’s haunting experiences of trauma and care work were peppered throughout Soleimani’s upbringing. She recalls how her mother would often rescue injured wildlife – those hit by cars or tortured by individuals – setting up a makeshift hospital on the kitchen table to nurse them back to health or attempt to, while recanting painful stories. The power of solidarity and kinship became formative values for Soleimani. By casting the wildlife, the women’s stories who are either incarcerated or have been freed in Iran in the Women, Life, Freedom movement and her mother as the protagonists in Flyways they each embody an autonomy that speculate on time, political choice or forms of escape.

In one meticulously layered photograph titled Correspondents, a looming shadow of an aeroplane draws our gaze across tessellated patches of white and blue sky flecked with seagulls. Some seagulls are woven into the texture of the paper, sunken into the background, while others appear as more prominent cutouts. As our gaze shifts downward, a yellow parakeet perches on a vibrant yellow mailbox with a bright red handle. Peering inquisitively into the open mailbox, it reveals fragments of letters and bird feed spilling out. More correspondence, written in Arabic, becomes visible as another parakeet, with white feathers and blue specks, nestles within the boundaries of the image. In the far-left corner, almost at the periphery, a small photograph of a man standing by a car and pointing into the distance brings the image full circle, back to the blue-specked sky. I later learn these parakeets named “happy” and “b-day” were dropped off in a gift bag on Soleimani’s doorstep, discarded as leftovers from a bygone present and become one of the thousands of birds and wildlife she cares for in any given year at Congress of the Birds.

Her theatrical, three-dimensional tableaux, hand built in her studio, are often large and complex stages filled with signs and symbols, each pointing to a different narrative. Her research typically involves hours spent trawling through Google Maps, enlarging images to pinpoint the exact locations these women describe in their harrowing stories. With limited information - markers like trees or descriptions of pathways as the only clues - she painstakingly reconstructs the places where these women were imprisoned or tortured. In others, her focus shifts to how they recount their experiences to Soleimani, and it is this essence of collaboration that becomes crucial to navigating the emotional landscape as much as the physical plight.

In another of these complex photographs, her mother appears in an almost larger than life setting, her feet surrounded by a mountain of shredded snakeskins, each a perfectly tessellated dermis. On one arm, she holds remnants of old skin, while the other is encircled by a snake – the position of her mother’s body is gestural. The correlation is akin to the human body in the centre being a scale of judgement, reflecting the burden of weight between life and death. The background of this image is meticulously collaged with a green chequerboard pattern, featuring pastel drawings of snakes traversing up and down. Delving deeper, this chequerboard pattern has become recurrent in several photographs, referencing the ‘games’ individuals have to play under totalitarian dictatorships to escape or for their stories to find ‘flyways’ to travel. Alongside the egg-shaped mask, previously seen in her series Ghostwriter, specifically Noon-o-namak (bread and salt), 2021, this mask serves as a form of disguise to protect her mother’s identity. Despite living in exile for decades, the threat and precarity of persecution still looms.

Nestled amongst these works in the series are smaller, more intimately sized photographs of birds held delicately within Soleimani’s hands – some in recovery, others recently deceased. By focusing on their injuries – a broken beak, a crooked claw, an eye clouded with milky blue haze offer a stark moment of pause. These incidents of injuries are all too common: “window strikes are only one of the leading causes of neurological impairment and death for birds, sometimes, when birds hit windows, they lose their head feathers – they leave a residue on the glass of their feather oil and dander, and sometimes they hit so hard that their feathers get stuck to the glass”. These hyperfocused macro images, become a significant part of the overlapping Venn-diagram in which industrialisation and nature intersect with modernity and power.

Each year, as migratory birds take to the flyways across the world, they create speculative correspondence through their birdsong – yet more and more birds are injured along their flight paths. The vacillation of their journey altered or changed in lieu of hospitals, apartment buildings, habitat loss and construction. Soleimani reflects: “Despite birds possessing far richer and more complex vision than humans do, they cannot see glass, and in general are looking for movement and not solid objects. As a result, skyscrapers and other office buildings are responsible for enormous death tolls. When I think of industry, I immediately go to the work I do with birds, because I am genuinely cursing industry for being such a destructive thing. When I think about labour, I think about the work I am doing. The history of migrant labour in particular draws me back to the ‘Women Life Freedom’ movement. To acknowledge the women that have been in solitary confinement or persecuted for their actions”.

What becomes apparent in Flyways is the emergence of new models of medical, aesthetic and ethical practices of repair. Soleimani’s labyrinthine structures of coding, code-switching and the embedding of narratives into her works continuously oscillates as new information, experiences and censored truths rise to the surface.

A free bird leaps

on the back of the wind

and floats downstream

till the current ends

and dips his wing

in the orange sun rays

and dares to claim the sky.

- Maya Angelou⁴

_______

¹ The Women, Life Freedom or Jin, Jiyan, Azadî movement in Iran advocates for gender equality, human rights, and freedom from oppressive government policies. It gained widespread international attention after the death of Mahsa Amini in September 2022, a young Kurdish woman who died in custody following her arrest by Iran's "morality police" for allegedly violating the country's strict dress code. Her death sparked a wave of protests across Iran, led by women and youth, who demanded justice and the right to autonomy over their own lives and bodies.

² Maya Angelou, "Caged Bird” from Shaker, Why Don’t You Sing?. The Complete Collected Poems of Maya Angelou, USA: Random House Inc, 1994.

³ Sheida Soleimani founded Congress of the Birds, a wild bird clinic that provides medical and rehabilitative care to over 2000 wild birds a year, operating from Providence, Rhode Island. The clinic’s name is inspired by the Persian poem Conference of the Birds written in c.1177 CE. Each bird named in the poem represents a human fault, eventually learning that they should all work together and no one species is superior to the other.

⁴ Angelou, ibid.

10 Oct 2025 – 21 Mar 2026

A free exhibition examining political dissent and erasure through the idea of collage

Banner image: Sheida Soleimani, Correspondents [detail] from the series Flyways, 2024. © Sheida Soleimani. Courtesy the artist and Edel Assanti.

Images on page all © Sheida Soleimani: 1) Sheida Soleimani, Safehouse, from the series Flyways, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Edel Assanti. 2) Sheida Soleimani, Correspondents, from the series Flyways, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Edel Assanti. 3) Sheida Soleimani, Magistrates, from the series Flyways, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Edel Assanti. 4) Sheida Soleimani, Misunderstanding, from the series Flyways, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Edel Assanti.

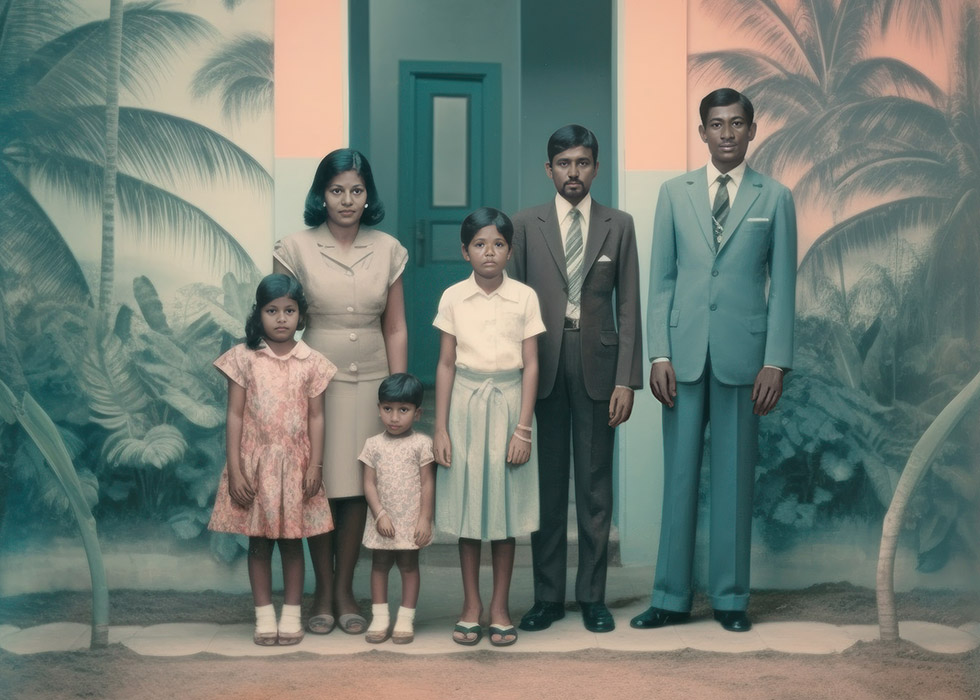

Exhibition: Sabrina Tirvengadum and Mark Allred, Family [detail], 2023. © and courtesy the artists.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.