To coincide with Autograph’s exhibition by Rotimi Fani-Kayode, we commissioned this text from Oumou Longley, exploring the context of Brixton in the 1970s and ‘80s, which provided the backdrop to Fani-Kayode’s work.

The exhibition, Rotimi Fani-Kayode: The Studio – Staging Desire is on display at Autograph until 22 March 2025.

‘I had set up an opposition between mourning and celebration. But actually they’re completely part of the same thing.’

– Mary Stevens¹

I’m not sure if there’s a word that perfectly summarises the connection between sadness and happiness, loss and life, but I’ve been reaching for it. It’s something I’ve been continuously struck by when exploring the histories of Olive Morris and the Brixton Black Women’s Group (BBWG), who collectively fought for the liberation of marginalised communities in Brixton in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

There’s a moment in which we connect with figures of the past, only to be struck by a grief that they are no longer around, that we didn’t know them sooner, that we have been robbed of a trove of representation. A grief that is perhaps only amplified when considering the social oppression and hardship under which their work emerges. A grief that is continued in our present attempts to make sense of the broader social, political and literal grief imposed upon marginalised and ‘othered’ bodies. It’s a dizzying spiral that invites political inertia. It feels as though society inevitably attempts to suture Blackness to suffering and loss in a way that often doesn’t align with embodied experiences of Blackness. Because as much as hardship has existed, there’s been a consistent, steady inversion of this narrative, throughout legacies of Black history.

"Life almost required a level of political activism from Brixton’s inhabitants for survival"

Across the ‘70s and into the '80s, Brixton became home to a new generation of Black Britons, working class, queer and marginalised communities. They existed within an environment of state-sanctioned neglect, underfunding, over-policing and racial tension, resulting in their stifling and mistreatment. As such, life almost required a level of political activism from Brixton’s inhabitants for survival.

By the ‘70s, Lambeth was ‘one of the most heavily squatted boroughs in the city’² and for many of those active, squatting was undertaken not ‘so much as a revolutionary act, but more as a need’.³ Organisations such as the British Black Panthers and the BBWG congregated in Brixton, and it became an epicentre of political activism and resistance. On Railton Road alone, squatted properties provided the headquarters for the Panthers and meeting space for the BBWG, amongst other notable presences. Nearly a decade later, with the support of the Brixton Housing Co-operative, Rotimi Fani-Kayode set up his home and photography studio on Railton Road. There was a temporal energy of action, motion and change - where space was claimed in an environment that attempted to deny your right to exist.

According to Stella Dadzie, a BBWG member whose oral history can be found at Black Cultural Archives, racism was shaping their lives.² Yet, in many ways, racism did not define them. Political action and collective accountability were woven into their day-to-day existence. For members of the BBWG, campaigning was as simple as witnessing a problem, and starting a group to address it; intervening in the lives of Black women and their intersecting communities, responding to police brutality, housing rights and discrimination in the education system.

This radical political action often took place in homes, dining rooms and via catch-up calls over landline phones - unaware of the enduring social impact it would leave behind. There was a connection between the personal and political, because their persons were highly politicised. And it makes sense to me that on the fringes of traditional society, where your existence is positioned as a challenge to conventional British structures, you inhabit life in a way that creates inherent potential for creativity, action, adaptability and change.

In legacies of Black history, political hardship and loss has been in continuous tandem with a tremendous amount of community action and life - which makes me consider the connection between the two dynamics. Much of the BBWG’s work is recounted through limited archival information, oral histories, and fragmented memories that carry the burden of years of erasure and social ignorance to their stories. Their legacy is frequently told through the narrative of Olive Morris, a founding member of the group who passed away on 12 July 1979 at just 27 years old, after a short battle with cancer. As such, loss and grief have appeared as present parts of Morris' narrative as well as the wider BBWG narrative; it permeates archival material, it feeds the urgency to remember, to make significant.

Yet the oral histories that make up the Olive Morris Collection at Lambeth Archives are vibrant and personal, they form a political legacy told through an intimate narrative of collective mourning. Within these embodiments of Blackness, loss is not just political, but a highly personal endeavour. And perhaps it’s an acknowledgement of this that allows us to claim agency over the hardships we face. The interpersonal grief found in both Olive’s and the BBWG’s history is used as a material that is formative, that is textural, that glues their stories together, that is continually expressed through solidarity and collective recognition.

In 1989, nearly ten years after Olive passed, Fani-Kayode followed, in a wave of Black men who died during the HIV/AIDS crisis of the ‘80s and ‘90s. Reflecting upon this moment, the photographer and radical archivist, Ajamu X, points out that though Fani-Kayode’s death was traumatic, ‘not all the memories that come with a person’ are, again reminding me that when we personalise loss, we are more easily able to utilise and manoeuvre it.

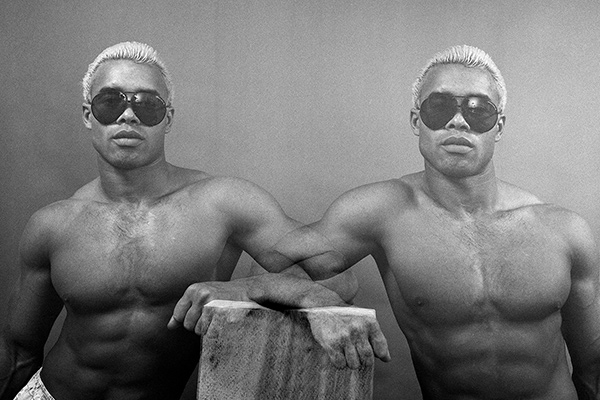

As this new exhibition at Autograph makes clear, Fani-Kayode’s life and loss was twinned with rage and desire. When Ajamu modelled for Fani-Kayode at his flat and studio in Brixton, the two of them enacted a power and presence that subverted the state’s insistance on silencing and blinding us to Black queer bodies. They balanced the social ‘death’ that results from state racism and homophobia, in a generation heavily impacted by HIV/AIDS, with an equal if not transcendent amount of vibrance and life. In the same interview, fellow archivist and filmmaker Topher Campbell adds ‘It’s a very Black thing…bringing together celebration and loss'. It’s an energy Ajamu and Campbell channelled into the creation of the rukus! Archive, preserving and making visible decades of personally collected Black LGBTQ+ ephemera for public acknowledgment and appreciation.

"Ajamu and Rotimi Fani-Kayode balanced the social ‘death’ that results from state racism and homophobia with an equal if not transcendent amount of vibrance and life"

In many ways, Black communities have utilised grief as a political and social material for action and empowerment. I return to the opening quote from Mary Stevens, made after her conversation with Ajamu and Campbell about rukus! and trauma in the Black queer experience: ‘I had set up an opposition between mourning and celebration. But actually they’re completely part of the same thing’.

Arguably (though not exclusively), it’s through a lack of visibility that we assert and fight to render ourselves visible; it’s in loss that we are able to recognise value, to find our own space, and to hold onto our community. I say this not to trivialize, dwell in or fetishize Black trauma, but to acknowledge and respond to the inevitable loss and grief that it is to be a human. By exploring loss as a material in the Black imaginary – where despite loss, through it, or even before it, comes a remarkable amount of life, creation, and connectivity – we recognise the possibilities to transcend it.

________

¹ Mary Stevens, p.284 in Ajamu X, Topher Campbell, and Mary Stevens, “Love and Lubrication in the Archives, or rukus!: A Black Queer Archive for the United Kingdom”. Archivaria 68 (January), 2010, pp.271-94.

² Milo Miller, Fairies, Feminists & Queer Anarchists: Geographies of Squatting in Brixton, South London. PhD Thesis, University of Nottingham, 2021, p.51.

³ Sandra Hurst, Do You Remember Olive Morris? Oral History Project [Transcript, p.3]. Interviewed by Remembering Olive Collective, 1 October 2009. IV/279/2/4/1, Olive Morris Collection. London: Lambeth Archives.

⁴ Stella Dadzie, Oral Histories of the Black Women's Movement: The Heart of the Race, 2009-2010 [Transcript p.26]. Interviewed by Mia Morris, March 2009. ORAL/1/12, Black Cultural Archives.

⁵ Ajamu X, p.283 in Archivaria 68, as above

⁶ Topher Campbell, p.283 in Archivaria 68, as above

Oumou is a writer, researcher and creative practitioner interested in the messy and fugitive ways that Black life is documented, in both personal and cultural archives. Oumou’s curiosity in this began on the LSE MSc Gender in 2018, where their research into Black British activist Olive Morris - available in the Feminist Review - began.

In 2021 Oumou produced an audio piece about Morris titled ‘Voices of the Archive’ for the ICA and BBC New Creatives Scheme, which premiered on BBC Introducing Arts radio. In 2022, Oumou expanded this work into a 10-day installation in Brixton Market for Lambeth Windrush. Oumou is interested in the multi-media, creative capacities of archiving. They recently shared oral history research on an LSE panel that celebrated ‘Legacies of the Brixton Black Women’s Group’ and seek to reflect on the intimacy and informality of spaces that have preserved Black histories, where institutions have failed to.

31 Oct 2024 - 22 Mar 2025

Free exhibition

Banner image: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled [detail], 1988. © Rotimi Fani- Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London.

Images on page: 1) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled, 1988. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London. 2) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled, c. 1988-1989. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London. 3) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled, 1988. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London. 4) Courtesy Oumou Longley. 5) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled [detail], 1988. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.