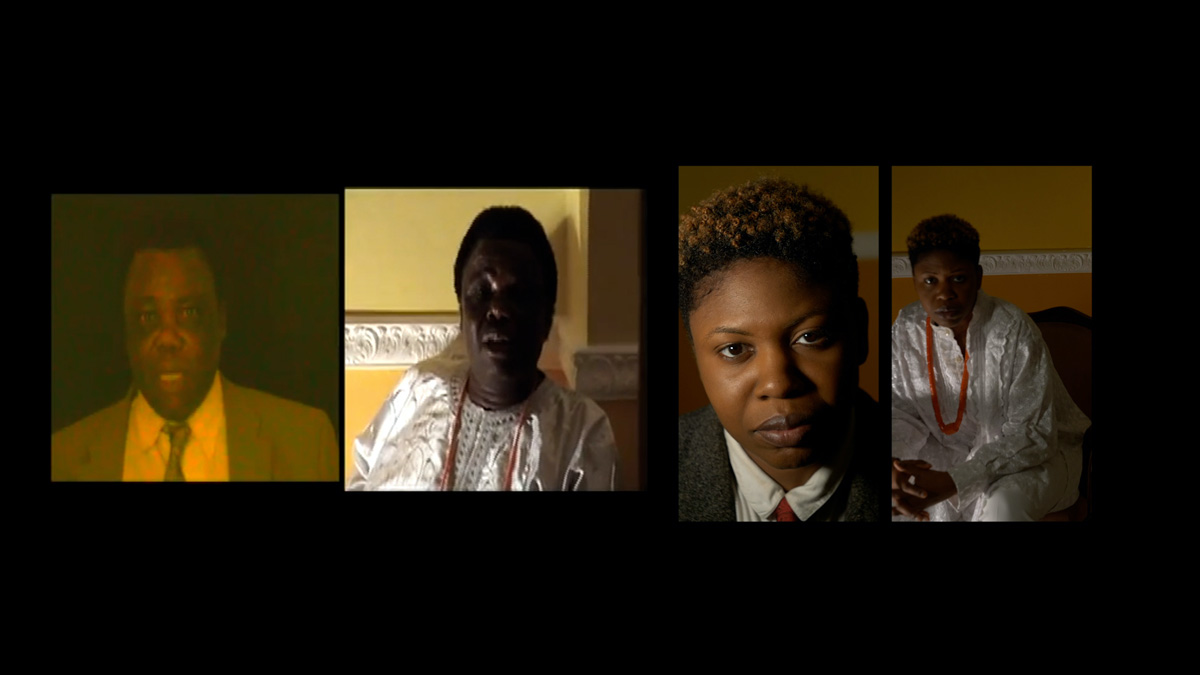

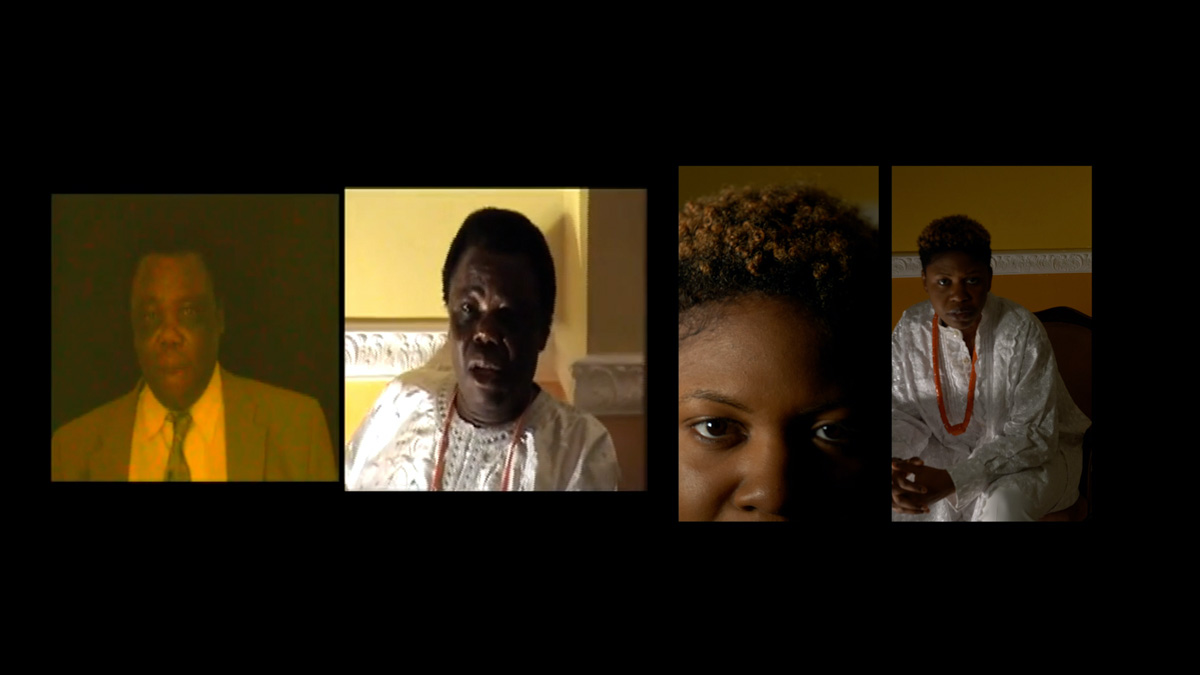

At the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, Lori returned to her family home in Essex, south-east England. As one of ten artists creating new work for our commissioning project Care | Contagion | Community — Self & Other, she staged two new moving image works which explore her relationship with her father: The Lines Between Us (2020) and I, Becoming You (2020). Revisiting their shared lineage of philosophy books, Lori’s performative re-enactments address themes such as family, culture, and diaspora alongside politics of identity, gender, class, privilege and education.

Filmmaker Campbell X has followed Ope Lori’s work over many years. Here, in this in-depth conversation the two artists discuss key themes in these new film works, focusing on politics of identity, sexual and cultural difference, as well as questions of intimacy in Lori’s art practice and the challenges of the education system.

Campbell X is a writer/director who directed the award-winning queer urban romantic comedy feature film Stud Life, voted by The Guardian as one of the top 10 Black British feature films ever made. It was also in Vogue magazine as one of the best films to watch in 2020, and selected by the British Film Institute as one of the top 8 queer films to view while we were all on lockdown.

See the full artist commission by Ope Lori

Read curator Renée Mussai's response to Lori's commissioned works

Renée Mussai introduces the new artist commissions in a curatorial essay One (Pandemic) Year On...

Read the introduction to the Care | Contagion | Community project

Visit the Care | Contagion | Community — Self & Other exhibition at Autograph's gallery

Can you spare a few moments? Autograph is carrying out a survey to better understand who our digital audiences are. The survey should take no longer than five minutes to complete. Anything you tell us will be kept confidential, is anonymous and will only be used for research purposes.

The information you provide will be held by Autograph and The Audience Agency, who are running the survey on our behalf. In compliance with GDPR, your data will be stored securely and will only be used for the purposes it was given.

You can take the survey here. Thank you!

Images: from Ope Lori's commission, The Lines Between Us / I, Becoming You, 2020. Film, © and courtesy the artist, commissioned by Autograph for Care | Contagion | Community – Self & Other: 1, 3-5) Film stills from I, Becoming You, 2020. Film, 5' 4". 2, 6) Film stills from The Lines Between Us, 2020. Film, 16' 11".

Other page images: 7 ) Courtesy Campbell X.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.