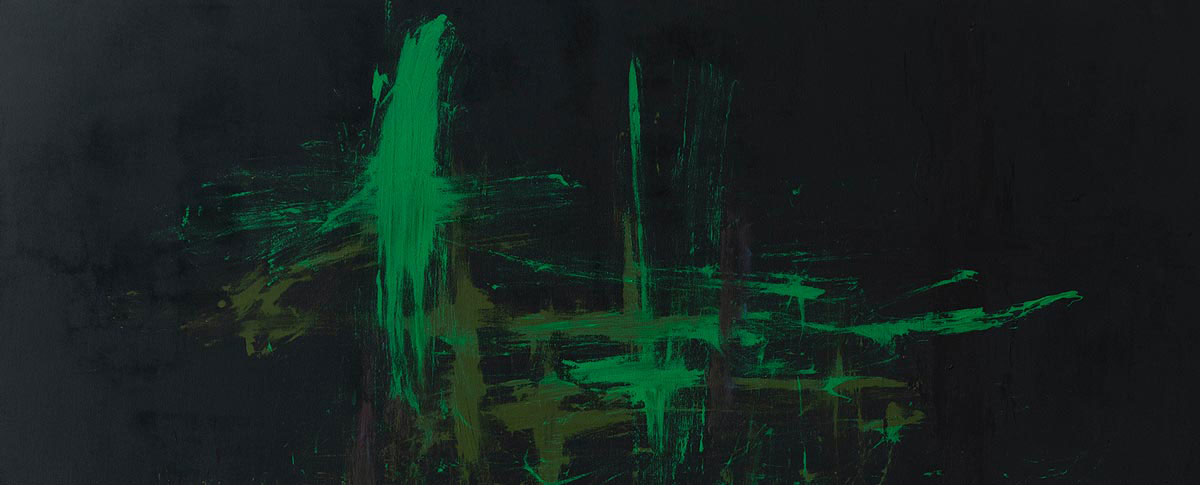

Othello De'Souza-Hartley, detail from Study 17 (Blind, but I can See), 2020. Commissioned by Autograph.

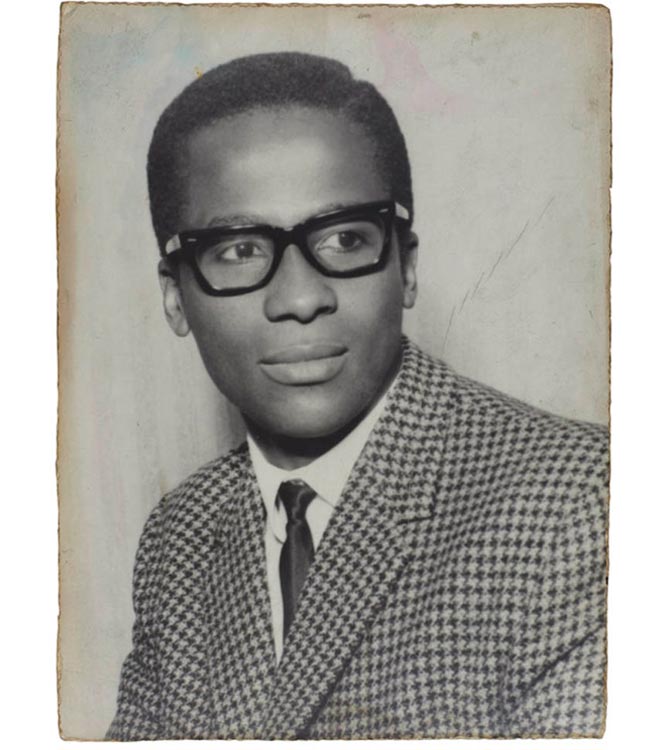

Othello De'Souza-Hartley, detail from Study 17 (Blind, but I can See), 2020. Commissioned by Autograph. Nevil Hartley, London, 1960

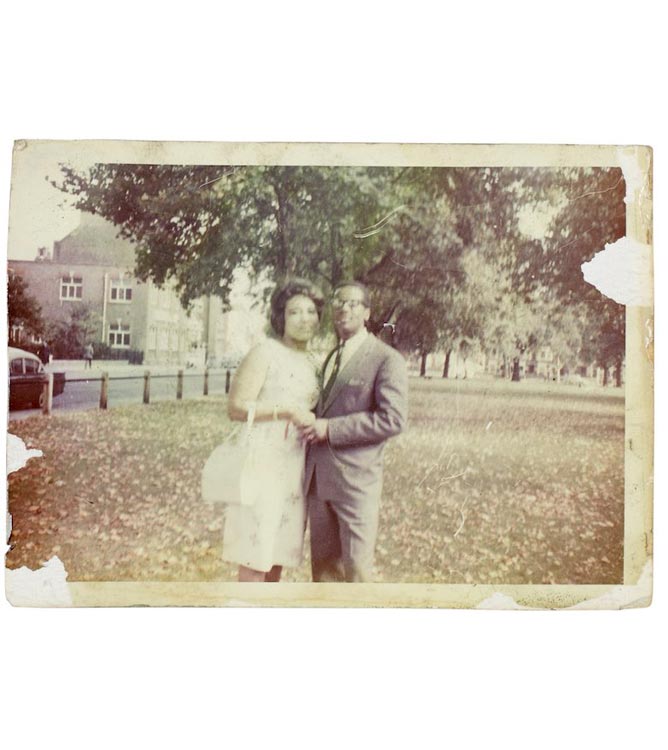

Nevil Hartley, London, 1960 Lena and Nevil Hartley in Shepherds Bush, London, 1966

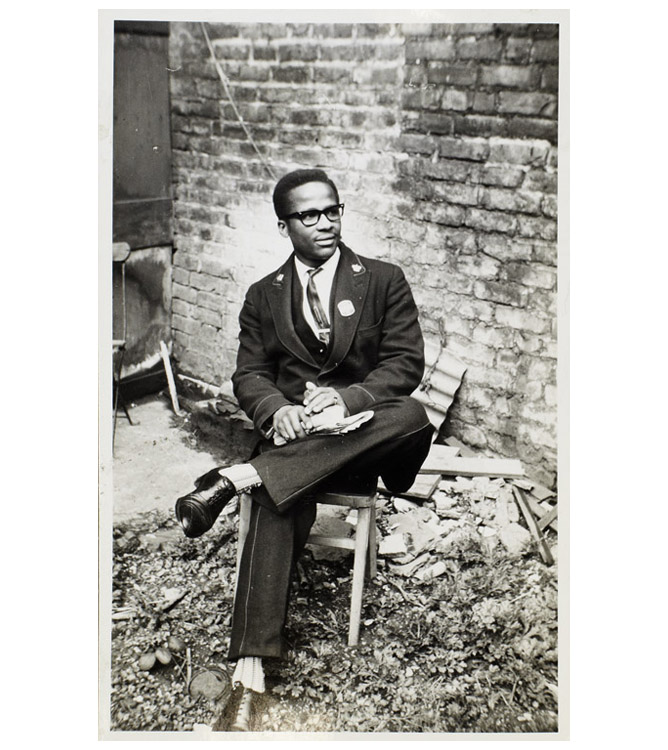

Lena and Nevil Hartley in Shepherds Bush, London, 1966 Nevil Hartley, London, 1960s

Nevil Hartley, London, 1960s

Image captions: Works from Othello De'Souza-Hartley's commission Blind, but I can See, 2020, © and courtesy the artist, commissioned by Autograph for Care | Contagion | Community — Self & Other: 1) Film still from: Blind but I can see, 2020. Video, 5' 44". 2) Room, 2020. C-type print, 20 x 24 inches. 3) Study 17 (Blind, but I can See) [detail], 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 48 inches. 7-9) Absence, 2020. Triptych, C-type print, each 20 x 24 inches. 11) Garden [detail], 2020. C-type print, 20 x 24 inches.

Other page images: 4) Nevil Hartley, London, 1960. Courtesy of Nevil Family Archive. 5) Lena and Nevil Hartley in Shepherds Bush, London, 1966. Courtesy of Nevil Family Archive. 6) Nevil Hartley, London, 1960s. Courtesy of Nevil Family Archive. 10) Othello De'Souza-Hartley, Steel Works from the series Masculinity, 2013. © and courtesy the artist.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.