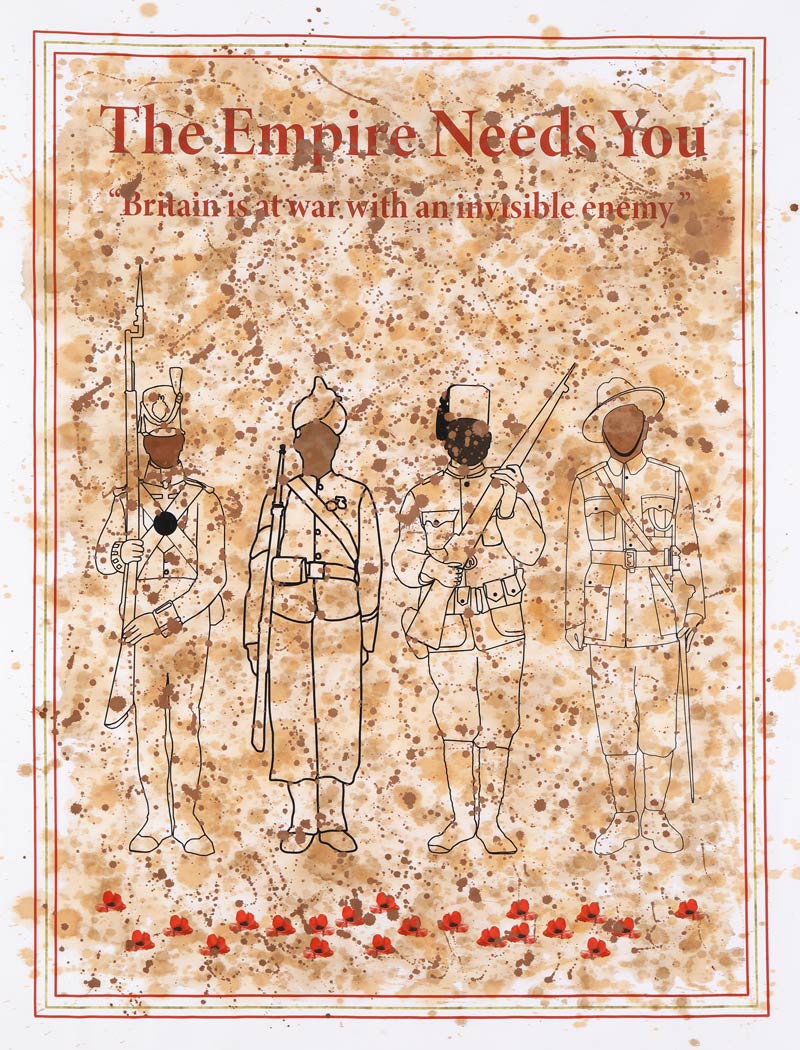

The Empire Needs You, 2020. Commissioned by Autograph.

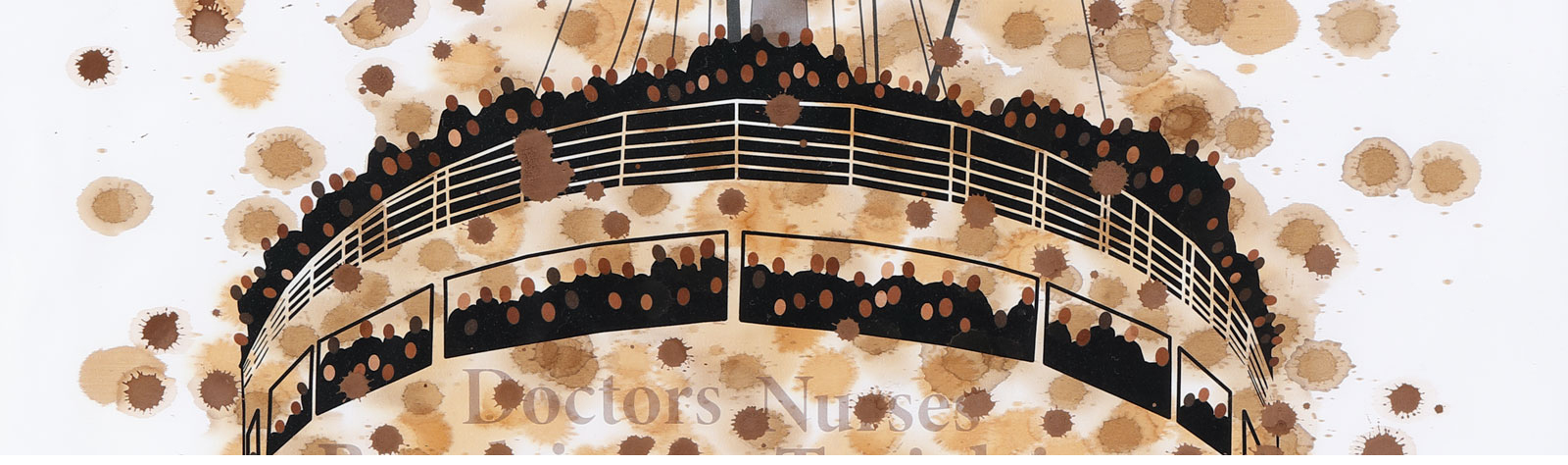

The Empire Needs You, 2020. Commissioned by Autograph. Your NHS Needs You, 2020. Commissioned by Autograph.

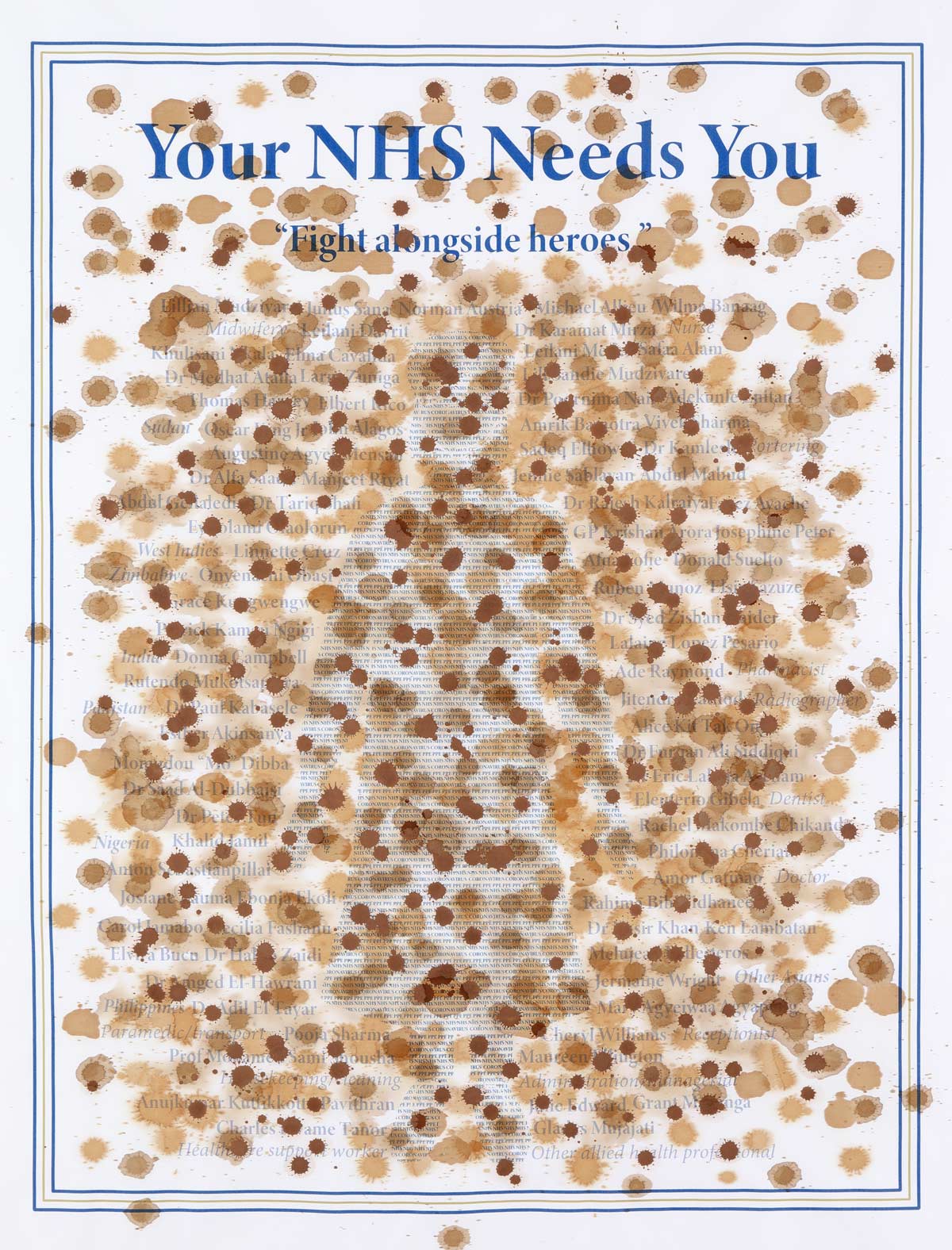

Your NHS Needs You, 2020. Commissioned by Autograph.

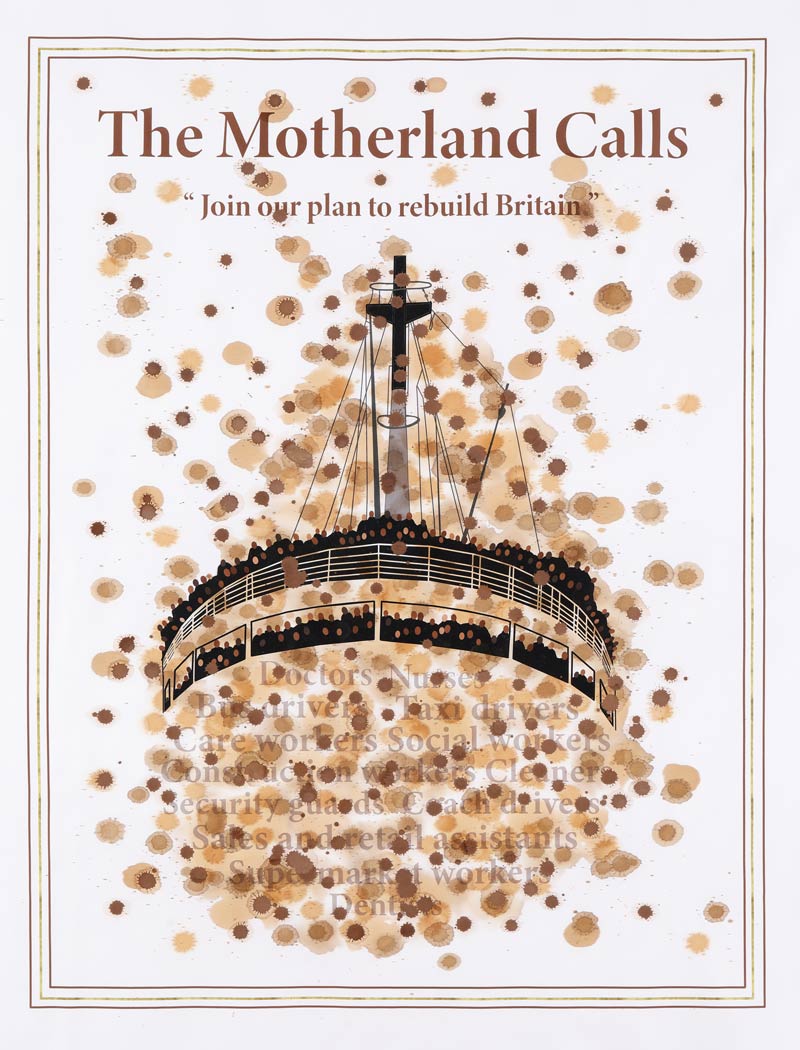

The Motherland Calls [detail], 2020. Commissioned by Autograph

The Motherland Calls [detail], 2020. Commissioned by Autograph

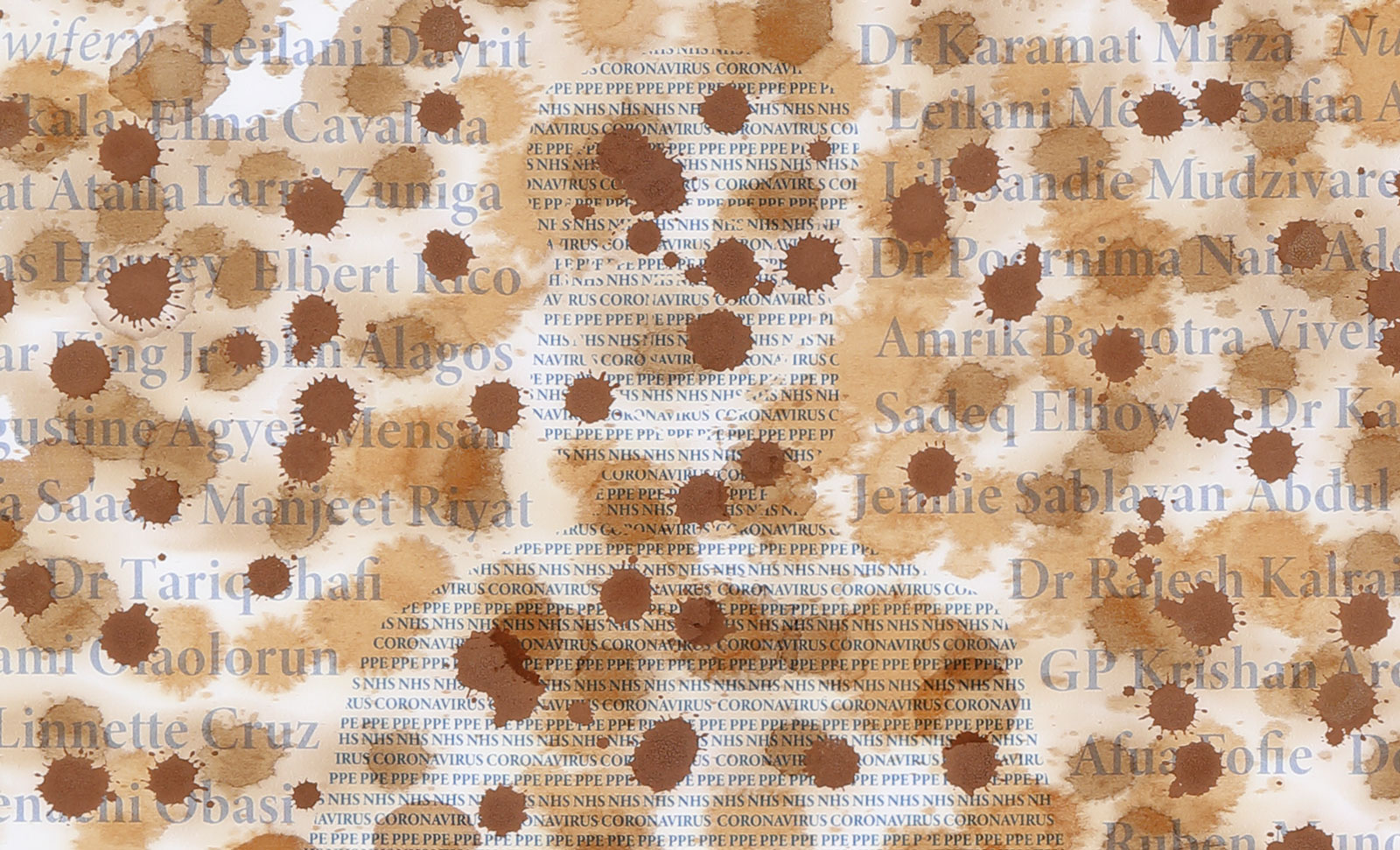

Your NHS Needs You [detail], 2020

Your NHS Needs You [detail], 2020

Image captions: Works from Aida Silvestri's commission Contagion: Colour on the Front Line, 2020, © and courtesy the artist, commissioned by Autograph for Care | Contagion | Community — Self & Other: 1) Cacao [detail], 2020. Cacao and pigment ink on cotton fabric; 50 x 65 cm. 2) The Motherland Calls, 2020. Cacao, coffee, tea, sugar, tobacco and pigment ink on cotton fabric; 79 x 102 cm. 3) Sugar, 2020. Sugar and pigment ink on cotton fabric; 50 x 65 cm. 4) A Great Leveller, 2020. Cacao, coffee, tea, sugar and tobacco and pigment ink on cotton fabric; 79 x 102 cm. 5) The Empire Needs You, 2020. Cacao, coffee, tea, sugar, tobacco and pigment ink on cotton fabric; 79 x 102 cm. 6) Your NHS Needs You, 2020. Cacao, coffee, tea, sugar, tobacco and pigment ink on cotton fabric; 79 x 102 cm. 7) A Great Leveller [detail], 2020. Cacao, coffee, tea, sugar and tobacco and pigment ink on cotton fabric; 79 x 102 cm. 10) Tea, 2020. Tea and pigment ink on cotton fabric; 50 x 65 cm. 11) The Motherland Calls [detail], 2020. Cacao, coffee, tea, sugar, tobacco and pigment ink on cotton fabric; 79 x 102 cm. 12) Your NHS Needs You [detail], 2020. Cacao, coffee, tea, sugar, tobacco and pigment ink on cotton fabric; 79 x 102 cm.

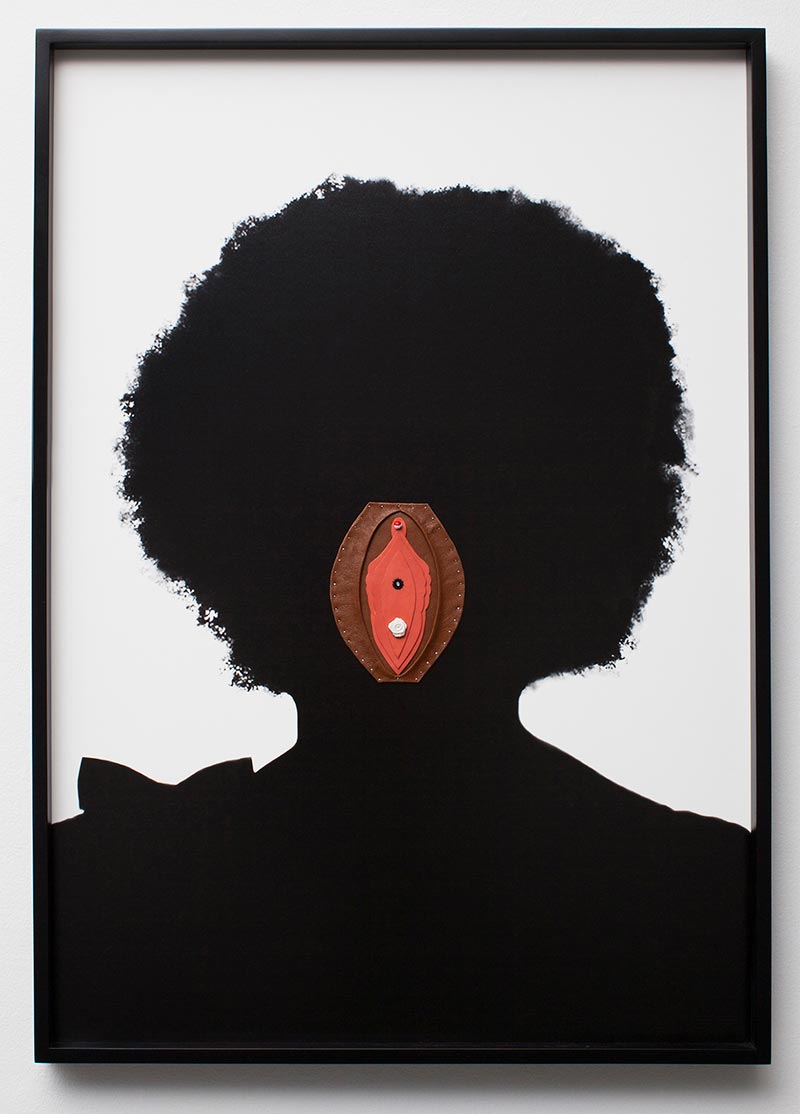

Other page images: 8) Aida Silvestri, TYPE I B. From the series Unsterile Clinic, 2016. 9) Aida Silvestri, Anghesom from the series Even This Will Pass, 2013.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.