Autograph's curator, Bindi Vora, speaks with the interdisciplinary Kenyan artist Syowia Kyambi about her work, considering the burden of working with colonial histories and creating space for artistic connections in Kenya’s contemporary art scene.

This conversation is part of a series supported by the British Council, sharing the work of women artists with ties to East Africa, and addressing issues of climate justice and the politics of representation. Find out more about the project here.

Bindi Vora (BV): Tell me about yourself.

Syowia Kyambi (SK): I've almost always been sure that I wanted to be an artist. In my early 20s, I had these brief moments where I wasn't sure about what I was doing, when I thought maybe I should be a radio jockey, or a television presenter. But at the core of it, I always knew that I had to make something. It wasn't always ‘pretty’ and there were times when I was making very instinctively and intuitively. I think I was connecting to a kind of spiritual realm, but at the same time I felt I had little control or understanding of what kind of energy I was tapping into, and that was frightening. This resulted in some of the earlier sculptural works I was making in 2003 which dealt with circular forms, using plaster of Paris and wood that incorporated menstrual blood. I ended up running away from that type of process, as I wanted to understand more about the impact of positive and negative energy. However, I don't think I have ever returned to that place of making in that way, ever again.

Instead, I began a journey that delved into a long process of understanding my family lineage. I think that came about because I was always being framed or questioned about my identity. I was looking for a language to articulate a wider understanding or a more nuanced understanding of who I am. I felt I had to understand what kind of spaces my parents were born into, and these environments may have shaped them and how they came together, to have me.

In my early 30s, I started to unpack my mother's and my father's lineage in a deeper manner, I also started to temporarily use the words Bantu and Germanic to describe my origin lines, to broaden the answers to questions like who am I? And where do I come from? My mother was born in 1942 in Hamburg, and my father was born in 1936 in Ukambani, Kenya. Those are very poignant historical times - times that still affect our present. It's probably the core reason I keep working with historical material in my practice, continuously returning to and unearthing histories to do with Britain, Germany and East Africa.

BV: In some ways these constructed histories narrate stories of difference, identity, race, home and memory – do you think the context of your upbringing and heritage has continued to influence the way you approach making work?

SK: Yes, of course, the context of my heritage has influenced my practice. Sometimes I have a deep desire to be free of that burden: of unearthing horrific histories; of creating work that makes me and other people uncomfortable; the burden of trying to repair something that is irreparable in a sense. It is a violence that produced a wound that can't be healed, in a sense. In my practice, there's a constant attempt to acknowledge these wounds and violations in order to come to a point of reconciliation, though I don't know if that will ever be fully possible. I keep being called back to those topics and themes.

I work with a lot of different materials but working with ceramics has provided perhaps the greatest relief. The materials are always used in relation to the research that I'm doing, and I explore whether that material actually translates meaning. I think there are a few repetitive materials and gestures that keep occurring in my practice. The use of ceramics, sisal, and mirrors for sure. I often use the mirror to include us - myself and the audience - in the present to connect to the past and sometimes to connect to the potentiality of the future. The archive and the use of photography is also an ever-present element in my process.

BV: We have touched upon some of the embodied experiences that you draw upon when making work, but I want to delve into the role of the archive within your research. You often turn towards archival imagery as a material. How do you settle upon an image to begin that process?

SK: When working with the photographic archive I tend to use several images that are always represented in close proximity to each other, so one photograph doesn't necessarily come before the other. In my work Infinity: Flashes of the Past (2007), which is part of the permanent collection at the Nairobi National Museum, I use scanned images from the museums photo archive. You never see a single image at any one time, it's always multiple images at the same time. This is similar in I've Heard Many Things About You, where the images don't have a beginning or an end even though the fabric is linear, as no image is given more importance than another.

There's something that attracts me to archives, it's such a sensory experience that it's hard to identify what it is that excites me about it, but when I'm working with archival material there's something important about the multiplicity in representation. I think it has to do with the feeling of being able to anchor yourself somewhere. That anchor may or may not be accurate because we know that archives have gaps and are built by people for specific reasons, but there's something about having a visual anchor to an image or an object from a time that's connected to where you come from that’s important; particularly when where you come from has either been erased or narrated in such a way that a large part of you is omitted, or a large part of your family’s story is omitted from the record, so the past remains unclear. I think that's where the root desire of working with archives stems from for me. It's an action to mark or shift something from the past in order to have a springboard towards your own future story.

I Have Heard Many Things About You, performance installation, Bremen, Germany, 2016. Video produced by Cantufan Klose

BV: We had a wonderful encounter in November 2022 during the closing weekend of the 59th Venice Biennale. Your work was staged as part of the Kenyan Pavilion, titled Exercises in Conversation, curated by Jimmy Ogonga. Your practice extends into multiple realms, could you tell us about some threads of your discourse?

SK: The work I presented for the Venice Biennale was titled I've Heard Many Things About You. I produced it in 2016, when the curator Ingmar Lähnemann commissioned me to make a site-specific response to Bremen, in the Städtische Galerie. It was an exhibition called Kabbo Ka Muwala: The Girl’s Basket: Migration and Mobility in Contemporary Art in Southern and Eastern Africa, a travelling group exhibition staged in Harare-Zimbabwe, Kampala-Uganda and Bremen-Germany. It was interesting because there were three curators who were working collaboratively on this project. Each of them selected a very different body of work of mine for each leg of the touring exhibition. There is a performative element in the work, a 14-metre-long veil that is like a patchwork of fabric stitched together. The images on top of it are mostly images from the Mohamed Amin Foundation, that Amin took in the 1980s in Namibia, placed alongside a document that the British wrote – a report about the atrocities the Germans committed in Namibia, which strongly references letters by Hendrik Witbooi responding to the genocide that was committed in Namibia. Witbooi was a large influence in my process, he was one of the nine chiefs of Namibia who was very resistant to colonial rule and as a result he was persecuted by both the British and the Germans.

He wrote a lot of letters to different generals in Germany and also to his counterpart chiefs in Namibia. One of the letters to a German general begins “I've heard many things about you”. When I was creating this body of work in 2016, I couldn't get to Namibia so I thought it was an apt sentence to have as a title because I too, have heard many things about Namibia but I couldn't physically engage with the space, with the land, with the people on the ground. This veil is suspended in the space in the form of a ship, using hangman noose ropes to suspend it in this form, attached to weighing scales which hold the fabric.

In the performance I wear a Herero dress that's worn in today’s time to commemorate the genocide, and walk through Bremen city. Starting from the Übersee-Museum (which is an ethnographic museum), I move through the railway station, to the centre of the city, past the Bismarck monument and the church into Böttcherstraße, which is part of the city that's a landmark tourist attraction. A lot of that part of the city’s buildings were erected in 1922 – 1931, financed by the exploits of colonisation. I continue across the bridge and into the contemporary gallery. In total, the performance is about four and a half hours long.

Before the piece is hung, I use a golden thread to highlight different kinds of texts or references in the texts that I think are important for the viewer. When the work is installed, you can't really see all of the components, echoing our stories, and the impossibility of being able to grasp the whole picture or completed history.

In terms of the pavilion in Venice, I was showing work alongside three other artists: Dickens Otieno, Kaloki Nyamai and Wanja Kimani. Jimmy Ogonga's curatorial subtext connects well with my piece, because it is asking for a conversation, provoking us to consider how we think about colonisation. There are some people who think that it's a thing of the past which doesn't affect us now - that we should get over it. I am often asked why I produce work like this, but equally there is an audience that is very engaged and wants to receive more information about what occurred in this time. It is these provocations through my practice that bring about a dialogue or conversation, alongside knowledge building, because a lot of these stories are omitted. I think it's a constant exercise, process and effort to converse. Conversing has to be exercised. Visually all of our works have elements of patchwork and stitching, which very much aligned with Ogonga's curatorial framework too.

BV: Why did stitching and draping become important in the reading of the work?

SK: Adolf Lüderitz was born in Bremen; he was the founder of Imperial Germany’s first colony as well as a merchant. He was responsible for the exportation of materials from Namibia during Germany's colonial rule of the country. The stitching and draping are important in the work because it is actually a silhouette of a boat. Named after the German merchant, Lüderitz town in southern Namibia was formerly a mining area with a railway track that took you all the way to the port, where raw materials were extracted from. Now it’s all but abandoned. So, the form of the stitching and draping is an attempt to capture the shape of a ghostly ship. Stitching is a repetitive action in my process. I think it's the binding of different layers together, an attempt to repair a breakage, where the repair process is left visible. It's conjoining things that are sometimes not obviously connected. Space is always a key part of my thought process when installing a work, I'm always thinking and utilising the existing architecture and forms that are present in the space. I think the trick is to know how fluid one can be with one's work: where do the boundaries have to be firm, and where can the boundaries be more lucid or free.

BV: Would you be able to speak about Untethered Magic?

SK: Untethered Magic is a space that is first and foremost a home. It's a residency space that is focused on exchange and as a result, in creating bridges and networks. It’s also a space for thinking about knowledge production and more equalised conditions. It's a sanctuary of sorts for myself and my colleagues, but also for artists who wish to spend time exploring their practice, their process and their research. It provides a rare space where there’s time to not necessarily know exactly what it is you're doing. We don't have a limitation on who can stay at Untethered Magic, it's for all sorts of practitioners. We're very interested in autonomy and self-sustainability. We don't work on a salary structure. I own the property that Untethered Magic operates from and we have six small residential structures that we also rent out to non-artists when we're not working on projects, which feeds back into the art’s ecosystem. We hope to break free from the traditional funding model for art support. We strive to support artists to work independently as much as possible. To achieve this, we are developing multiple revenue streams and support structures and networks, aiming to rely less on institutions. One potential outcome of this approach is that we may evolve into a de facto pseudo-institute or even a para-institute. Our primary efforts focus on achieving a certain level of autonomy, revolving around the development of six cabins, designed to serve as tiny homes for resident artists. These cabins are clad with recycled hardwood floorboards and windows sourced from my childhood home.

We are currently in the process of launching a project called JiJenge. The concept behind JiJenge is to announce an open call for a month-long fully funded residency at Untethered Magic, targeting artists and creative practitioners residing outside of Nairobi County within Kenya. In the Nairobi art scene, we don’t have many connections with creatives in other counties and as a creative myself, I’ve found it hard to develop myself and build networks. So, this initiative aims to address that, exposing artists to the Nairobi art community, helping them to build a network and enhance their artistic practice.

BV: Your practice questions notions of remembrance through multiple lines of enquiry: archives, language(s), and other participatory activities – could you speak about why this blending of process is important in your work?

SK: That's a very good question. I think I find multiplicity in practice very interesting, because we function in multiple ways. There's always a push which I feel is political, that makes you think you belong to a singular space or a singular system and that's simply not the nature of human beings. I think some of that is rooted in nationalism and some is rooted in capitalism and imperialism. In order for those systems to work well for themselves, they emphasise a narrative of singularity that is a form of propaganda. In reality, our lives are multiple – we can’t subscribe to a singular perspective, especially when we work with stories, language and archives. I suppose that's why I have always utilised multiple ways of inquiring and layered processes in my practice.

BV: I am interested in how your practice concurrently deals with questions of identity and perception in the broadest sense, but also raises important questions around geographical contexts in the way we experience time, difference, and marginality. Why is this important in your practice?

SK: As a contemporary art practitioner, there's a very strong desire to be easily categorised but I don’t think that should be the case. As human beings we are much more complex than singly identified categories, which in some ways circles back to that idea of multiplicity which we’ve just touched on. For me, there's a natural resistance to being marginalised or categorised because there's nothing marginal about the themes and topics that I'm dealing with. My process is multifaceted. There are multiple tools deployed at the same time. There are multiple thought processes and multiple conversations. It really takes time to unpack the work, time for an audience to engage with the work, time for me to create the work.

BV: You recently opened a solo exhibition at the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute (NCAI) titled Kaspale that explores the complexities and repercussions of silenced voices – could you tell us more about the installation you have developed for the exhibition and the concept of masking in your work?

SK: Kaspale is a character that I've been working on since 2019. I was doing some work at the MARKK Museum in Hamburg around the same time, where I was invited to participate in an exhibition called Amani: Traces of a Colonial Research Centre. The research centre that was built between 1902-1904 in Tanzania, in the Usambara Highlands. An anthropologist Prof. Dr. Paul Wenzel Geißler had been researching this space and its history and invited four artists to undertake a residency at Amani. However, I found it quite a violent act to export materials from Tanzania and reposition them back inside of an ethnographic museum, especially in the context of the times we are living through today. Instead, I asked them to host my residency at the MARKK Museum as I felt the need to develop a tool or mask that would support me in making an intervention in an ethnographic space as a contemporary African artist, and that's how Kaspale was birthed.

Kaspale is a creolization of a name, pale in Kiswahili meaning ‘there’. In Kenya, we have a lovely language called Sheng, which is a mixed language of Swahili, English and sometimes Kikuyu originating among the youth in Nairobi. It’s a language that is constantly changing, which is what I find so interesting about it. Through the intonations you can pinpoint the area of the city somebody grew up in, and how old they are according to the type of Sheng that they use. So, I created ‘pale’ into my own Sheng, using the English intonation of there which implies a question or exclamation mark. Kasperle in German is a joker or trickster character and similarly, Kaspale is my trickster character which I use as a tool of intervention. There are several trickster characters all over the world in all sorts of mythology, that different cultures have used to speak about things that are hard to speak about, or hear. Kaspale became a character I created for myself to engage with this ethnographic space in 2019 which then continued into other works.

The Kaspale Ancestors series is an ongoing body of work developed through the provocations put to me through the artist collective I was part of called What the hELL she DOing! During a remote studio visit the collective asked me: ‘Who is around Kaspale? Are they alone in the work that they do?’ It really enabled me to build kin and family around Kaspale, which is where the clay and wooden masks and some more recent ceramic sculptures of primordial forms came from.

Syowia Kyambi (b. Nairobi) is an interdisciplinary artist and curator who works across photography, video, drawing, sound, sculpture and performance installation. In Kyambi’s artistic practice history collapses into the contemporary through the interventions of mischievous and disruptive interlocutory agents who interrogate the legacy of hurt inflicted by colonial projects that still frame the wider political conjuncture of now. The work asks important questions about what is remembered, what is archived, and how we see the world anew. Rooted in her practice is a deep connection with the land, the earth and the idea of home.

Kyambi’s work is held in several private and public collections including the Robert Devereux Collection, London, the Kouvola Art Museum Collection, Finland, the National Museum of Kenya and with the Sindika Dokolo Foundation. She has taken up artist residencies and exhibited throughout Europe, Africa and the United States.

Autograph's curator, Bindi Vora, shares a series of conversations with women artists addressing issues of climate justice and the politics of representation in their work.

Find out more

Banner image: Syowia Kyambi, I Have Heard Many Things About You, performance, Bremen, Germany, 2016. Still detail from a video produced by Cantufan Klose.

Images on page: 1+2) Syowia Kyambi, Infinity: Flashes of the Past, installation view at Nairobi National Museum, 2007. 3) Syowia Kyambi, I Have Heard Many Things About You, performance installation, Bremen, Germany, 2016. Video produced by Cantufan Klose. 4+5) Syowia Kyambi, I Have Heard Many Things About You, performance stills, Bremen, Germany, 2016. Video produced by Cantufan Klose. 6) Ceramic works from the Kaspale series in the artist's studio, Nairobi, 2023. 7+8) Syowia Kyambi, Kaspale's Archive Intervention, postcard, 2019. 9) Syowia Kyambia, courtesy of the artist. Photo credit: Marlon Hall, 2022.

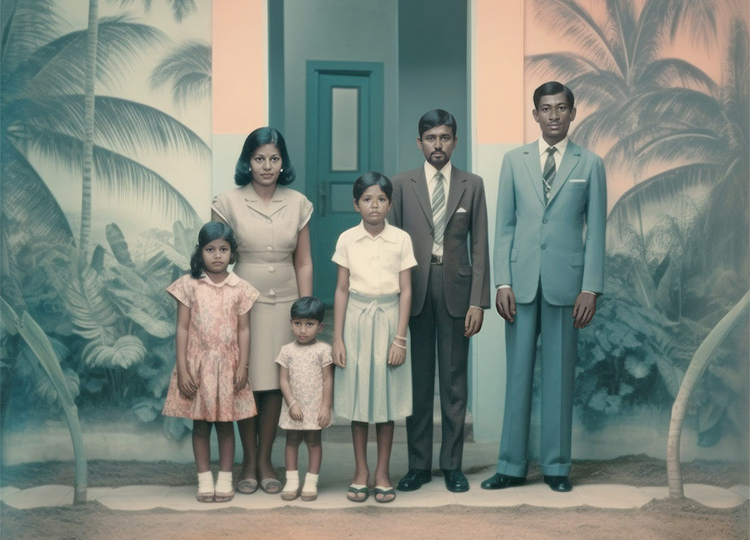

Part of the project: Sabrina Tirvengadum and Mark Allred, Family [detail], 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.