To coincide with Autograph’s current exhibition by Rotimi Fani-Kayode we commissioned this interview with Rotimi’s friend and model, Dennis Carney. Here Dennis speaks with Autograph’s Director, Mark Sealy, about London’s black queer creative community in the 1980s, and the significance of Rotimi’s tender depictions of black male bodies at a time of heightened oppression.

The exhibition, Rotimi Fani-Kayode: The Studio – Staging Desire is on display at Autograph until 22 March 2025.

Mark Sealy (MS): So Dennis, thank you for taking the time to talk to me today – it’s a pleasure to see you again. To get us started, perhaps you could tell me about your first encounter or memories of Rotimi Fani-Kayode? You were friends in the ‘80s, right?

Dennis Carney (DC): The very first time I met Rotimi, I will never forget it. It was in a black gay club called Stallions, in London's Soho area. This would have been 1985 or 86. And Rotimi was in this club in a black leather jacket, black leather trousers, and dreads. At that time you didn't really see a lot of black men walking the streets of London in full black leather. And he had the most beautiful dreads I've ever seen. In fact, he inspired me to grow my dreads - he started them off. How beautiful is that? I don't know how we got to talking, but we did, and from there we became friends.

MS: What was your friendship like?

DC: It was very special. I've never met anyone like him. He had such a gentleness about him, but he still stood out. I remember when he told me that he had studied under the American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, I was a bit shocked and challenged by that knowledge, given the controversy around Mapplethorpe’s work, but also impressed - it wasn’t something that I would have assumed he’d do.

MS: Can you tell me about how you came to model for him?

DC: My first shoot with him was when he was living in Tulse Hill on a council estate. He asked me to do it because he was really struggling to find black models who would be willing to pose nude. What a lot of people don't realise is that back then in the eighties, the idea of the black male nude was controversial - taboo even. Back then I was only 23 or 24. I'd never done anything like that before. I was absolutely terrified by the prospect. But Rotimi made me feel comfortable and relaxed. It was a positive experience. The photos that came out of it were amazing.

MS: That’s really interesting to me, the radical nature of the black, male nude body. Because this was in the mid-eighties, when we were in the midst of a crisis with the HIV/AIDs epidemic. This is the moment of Mapplethorpe, but it’s also a moment of heightened police brutality against LGBT+ and black communities. This is at the height of stop and search, and the sus laws and only a few years after the Brixton riots of 1981 and 85. This is the moment where you really did feel, as a black person, that you were always under scrutiny. If you walked into a pub, a club, a café people would look you up and down. Even if it was a black space - people would look at you to make sure you're the right type of black person. So there's this degree of hyper-masculinity around how black men were presenting themselves – it was tough. So this tender moment when you are in the studio with Rotimi is quite intense. It's quite an act!

DC: Absolutely. And remember his studio was in his flat. So it was his personal space as well as a workspace.

MS: So when did you meet the poet, Essex Hemphill, who Rotimi photographed you with?

DC: That was a little later, when Essex came to London for his first tour. After Hemphill’s performance, there was an after party at writer, activist and community-builder Dirg Aaab-Richard’s house in Railton Road where Essex was staying. Dirg organised the tour and was working at the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre (BLGC). At that time, the BLGC was based out of Tottenham Town Hall, so that’s where the gig took place. Later, in 1992, the BLGC secured a permanent home which was in Peckham, on Bellenden Road.¹

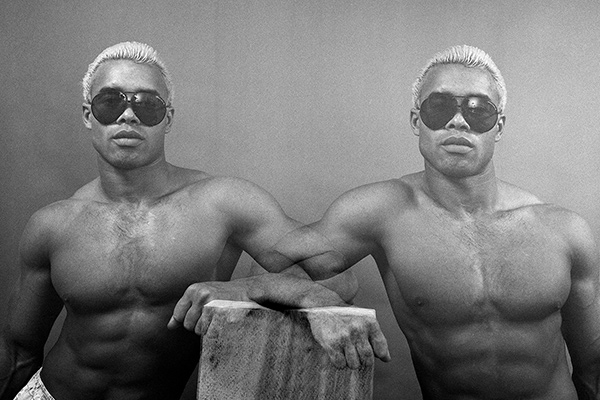

MS: So without the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre, there’s no Essex Hempel in London, there's no meeting between the two of you, and there would be no moment of Rotimi capturing that image. And that’s where these community networks are really important. These iconic images of you and Essex are currently on show at the Wexner Centre for the Arts in Ohio. They’re now celebrated and understood as this moment of transgressive engagement.

DC: That photo of me and Essex is really special to me. Because we had a romance, let's call it, whilst he was here, and he had a massive influence on my life. Him and Rotimi, actually, when I think about it, but more significantly Essex.

MS: And where were you living at this point?

DC: I was living in Stockwell in a Ujima housing association flat.² I don't really know how I got that flat, but I was really lucky – it was in this beautiful Georgian house. That’s where I was living at the time when I met Rotimi. So then I introduced Essex to Rotimi, and they got to talking. And that’s when the idea of all of us doing a photo shoot came about. So when that shoot happened, Essex and I were right in the middle of this passionate romance. So that's why that picture is so charged for me.³

MS: Can you say any more about the relationship between Rotimi and Alex Hirst?

DC: They were a couple and Alex lived in Clapham. I used to get invited to dinner and Alex would type up this menu and put out place cards. It was all very fancy. I'd never experienced that before. It wasn't a big place, but I remember I was hugely impressed by it, and that Alex took the time to do that. Rotimi and Alex had a loving relationship, but also collaborated as artists. Alex played a significant role in supporting Rotimi’s work – he was connected in the world of the gay press. And he was white, so that opened doors that might not have been as easily opened for Rotimi at that time.

MS: That’s interesting, because I find that, sometimes, people want to make things more simple than perhaps they were. And I’m keen not to deny the importance of Alex’s role in Rotimi’s work. I think they influenced one another’s work in significant ways.

DC: Absolutely, yes. In a lot of ways, they were each other’s muse, and they connected deeply on a cerebral and artistic level. Some of the earliest images from this time that I can remember are photographs of Rotimi and Alex stretched out on a couch together. And it was quite a radical thing at that time, because the politics were different to how they are now. For example, back then in America there was a massive organisation that had chapters in every city called the National Association of Black and White Men Together - their relationship was part of that zeitgeist in some ways.

MS: Did you get the sense that Rotimi was confident and comfortable with what he was doing in his work?

DC: Rotimi was extremely focused on using African iconography and culture to dismantle this hegemonic white gay narrative and to break some of the taboos around sexuality - and specifically homosexuality - in Africa or African cultures. That’s not to say he was always serious in his work. If I think of Rotimi, the first image I think of is the image of him with the white umbrella and his legs crossed. And what that reminds me of, was that there was a huge amount of laughter between us. He didn’t take himself too seriously – he was playful. But he also went through different phases with his work, so most of the early work was black and white, and then he went through a colour phase.

MS: Yes exactly - his early work was very much influenced by the different capacities of silver gelatin. So he was working with black and white printing. But the last chapter of his work, what I like to call the communion series, is very rich, very Rubens-esque. Very beautiful in terms of colour.

DC: And I would say that had a lot to do with him moving to Railton Road because - even though it wasn't a massive space - that flat facilitated his work. In order to get that flat, he had to be a member of Brixton Housing Co-op, so he was involved in the design of his space too.

MS: Right yes, because they were renovated. And Rotimi had the big bay window to the front and the large windows at the back of his flat, so lots of light coming in.

DC: Yeah and a tall ceiling, which made the room feel much bigger than it was.

MS: Perfect for photography.

DC: It was and he made it work for him. That played a big role in his work.

MS: So by the late eighties, Rotimi is becoming more well known; Ten.8 Magazine have published a few things, his book - Black Male/White Male - is published, a few exhibitions of his work have taken place and he’s involved in the Brixton Art Gallery which is a radical space: it’s queer friendly, it’s black friendly, it’s working class. At the same time there was Linda Bellos running Lambeth council – how radical is that – you know a mixed-race feminist and lesbian leader of a local authority. Imagine that now, people would be just cut to pieces!

DC: Brixton back then was interesting. None of that could happen today and I think it was because we were under the cosh of Thatcher. It really forced a lot of creativity.

MS: And it created relationships. People were trying to connect and be more open, I think. I do lament it a little bit. I mean, people were poor, and it was a tough time. Housing wasn't good, but it was available and social mobility was there.

DC: I often get asked to talk about black queer history and there's a narrative I really try to resist and that is this kind of victim narrative. Because Rotimi may have been a victim of the racism that existed in the field of photography at that time and it was a struggle for him to get his work out there because of that. But he succeeded to a large degree. He was making progress even with all of those challenges and struggle.

MS: Dennis thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me and share your memories of Rotimi.

DC: Well thank you. It’s been really good to talk about Rotimi because not many people know him or remember him. I just feel very blessed to have met him when I did, and for the friendship that we had. He's still very dear to me - I've got a poster on my wall from one of his exhibitions, as well as a self-portrait that Rotimi took. He's looking directly at the camera with his beautiful smile. I love that photo.

________

¹ The Black Lesbian and Gay Centre was a community centre in London that ran from 1985 to 2000. Their archive is held by the Bishopsgate Institute and can be browsed here.

² Ujima was Britain’s oldest and biggest black housing association, set up in 1977 with patronage from Benjamin Zephaniah and which sadly went bust in 2008.

³ For more on this image, you can listen to this podcast from Black and Gay, Back in the Day, featuring Dennis Carney.

31 Oct 2024 - 22 Mar 2025

Free exhibition

Banner image: Rotimi Fani-Kayode: The Studio - Staging Desire exhibition at Autograph, London. Curated by Mark Sealy. Photograph by Kate Elliott.

Images on page: 1) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled, 1988. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London. 2) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Dennis Carney and Essex Hemphill, Brixton, 1988. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London. 3) Rotimi Fani-Kayode: The Studio - Staging Desire exhibition at Autograph, London. Curated by Mark Sealy. Photograph by Kate Elliott. 4) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled, 1988. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London. 5) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Umbrella [self-portrait], 1987. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London. 6) Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Adebiyi, 1989. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London.

Visit the exhibition image: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled [detail], 1988. © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph, London.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.