Arpita Akhanda is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice explores the relationship between present experiences and historical trauma, particularly the legacy of displacement during the partition of India, where she is based.

Her series of works A Veil of Memories features in I Still Dream of Lost Vocabularies, Autograph’s current exhibition examining political dissent and erasure through the idea of collage.

Below, the artist speaks with Autograph’s Learning and Digital Engagement Manager, Livvy Murdoch, about using textiles and family archives to explore issues of trauma, gender and memory making.

This text was originally published in the exhibition newspaper which is available to purchase, and includes work by all thirteen artists featured in the show.

Livvy Murdoch (LM): Thank you for joining me for this transcontinental conversation Arpita. Three works from your series A Veil of Memories are being shown in our new exhibition I Still Dream of Lost Vocabularies – I wanted to begin by asking about the role your family archive has played in your practice.

Arpita Akhanda (AA): I have been working with my family archive for about six years now, but this work has mostly been with the records from my paternal side because I grew up with my paternal grandparents. We lived in a rented apartment all our life, so every time we moved from one house to another, one corner of the new apartment would be dedicated to these photographs, objects and albums. This collection always sparked curiosity in me as a child, so I asked my grandparents about it and came to better understand my family history and what home meant to my family, before partition. But I had very little knowledge about my maternal grandparents, so A Veil of Memories emerged from my desire to better understand them.

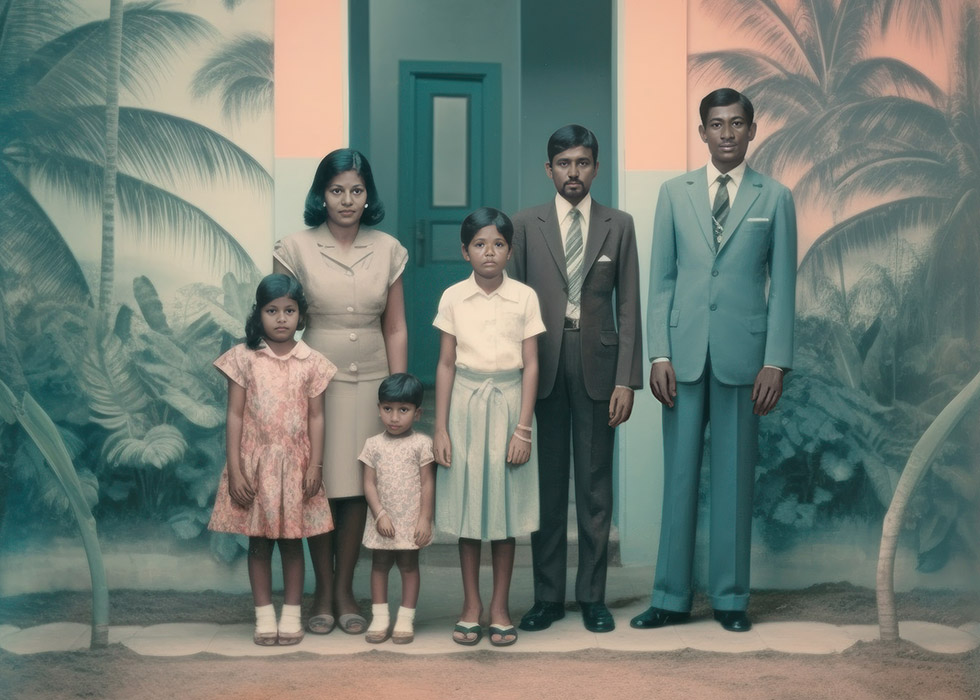

The photograph that features in this work was actually the first photograph that I saw of my maternal grandparents together. In 1953, my grandmother, Priti Banerjee, married my grandfather, Sadhan Kumar Banerjee, in what was East Pakistan but later became Bangladesh in 1971. As a young bride from the Indian side, she was asked to veil her face and identity not as an act of modesty but as a shield. It was a literal and symbolic tool of protection for her during partition – a time of heightened violence against women.

I never met my grandfather, he passed away before I was born, but he was from Faridpur in undivided Bengal. Although he was very young, he was part of the freedom struggle in his village, so when Bengal was divided he was forced to come over to Kolkata because of his activities and also to continue his studies. In a way, he had to veil his identity for survival too.

LM: What a complex context from which to start building a life together. You use the same portrait of your grandparents across the different works that make up A Veil of Memories, is there a reason for this repetition?

AA: The memories I work with often go through a lot of repetition. When an event like partition occurs in a person’s life, its impact tends to echo through time – both personally and politically – via objects and the recollection and sharing of events. Whenever I used to sit down for conversations with my grandparents, I noticed that the same memories would resurface in different forms. They were like motifs or patterns in a textile, familiar yet always slightly altered. Each iteration carried a new tone, detail or emotional weight.

I wanted to translate that sense of repetition into my work. That’s why you’ll often find the same archival images reappearing across different pieces and contexts. For me, it’s not about representing memory in a linear way, but about capturing how itself emerges, evolves and gets transmitted. I’m as interested in the process of remembering and reclaiming as I am in the memory itself.

At the same time, repetition is not only an act of addition, it’s also an act of erasure. Each layer builds upon and conceals what came before, creating a different kind of disappearance. I find that tension between repetition, layering and erasure deeply compelling, and it’s something I’m continuing to explore in my upcoming works as well.

LM: It feels particularly pertinent to consider ideas of erasure in relation to these troubled histories. In these works, you’ve woven vintage colonial era maps through your grandparents’ portrait, creating patterns that appear almost as absences – can you tell me more about these patterns?

AA: My grandmother was very into crocheting - everything in our house is covered with her crochets! So the patterns that you see in this work are all taken from the crocheted objects that she made. The weaving and crotchet patterns combine layers of history in my work, with a ‘hide-and-seek’ effect. I understand my personal archive as the warp and the more institutional or official records like the maps are the weft – by weaving them together I create a third layer or narrative, one that can reflect on the shifting of cartographies and what this meant for people’s identities. It becomes a metaphor for the many different types of transitions and journeys that migrants had to make.

LM: I'm glad your family valued their archive and these crotched objects enough to keep them, despite moving home numerous times. In a way you’re continuing and adding to a family tradition, by thinking through and working with techniques associated with textiles.

AA: Yes absolutely, especially as my paternal grandmother made embroideries and was also a kantha maker, which is a quilt that was very popular in Bengal. I'm not a trained weaver - I did my bachelor's and master's in painting, but I'm slowly transitioning into textiles. Last year was the first time I worked on a hand loom and I'm currently working on a large digital Jacquard tapestry titled The Curtain Falls, which will be around 300 x 300 cm when it’s completed.

I’m trying to better understand how gender plays a role in memory making and preservation. Family archives in the form of photographs and writing were more likely to record men’s histories, especially within Indian or South Asian family narratives. Women’s stories tend to be found more in the form of textiles, food and oral storytelling traditions.

When I started working with my archive, my paternal grandfather left a lot of photographs and text, so I began working with that, but I quickly started to feel a void: what happened to my grandmother? What is her memory? What is her story? What objects might she have left behind? I think she probably experienced quite a lot of violence and that might explain in part why stories like hers get lost, because of the trauma and taboos in documenting those experiences. When I used to sleep next to her on summer nights, there would often be power cuts, so she would turn a hand fan and slowly - in these moments in the dark with no electricity - she would begin to tell stories and create narratives that drew on some of her memories from the village where she grew up.

LM: So those were your moments of deeper connection? Do you think it became permitted for her to share in those moments, as it was almost like a bedtime story?

AA: Yes, it provided a way for her to tell her story, but it could be veiled with elements of fiction to make her feel safer. The story would always start with a King or a Queen, or it would be a story about a monster set in her village. But the details of the story were always so vivid; the when, the what and the who were all told as clear recollections and so I came to understand how she fled. I would always wonder what gets triggered, or what shifts in those moments? What caused the space to feel safe for her? In a recent work titled Hath-Pakha (2023 - ongoing) I made a hand fan for people to use. You can come and fan yourself and listen to memories and recordings I took during conversations with grandmothers from both sides of my family. The audio plays as you make the turning motion with the fan.

LM: What a beautiful way of honouring those conversations. Do you think the intricate processes you work with make you feel closer to your grandparents?

AA: Absolutely. Every time. I want to leave these memories for the next generation as well, because they're never going to meet my grandparents. I want them to have access to their story beyond just the sense of beauty or nostalgia that we feel when looking at family photographs. Each and every image has a story, which is part of something much bigger. I want future generations to understand the historical context and that's where I feel like the work I make is important. It goes beyond my own histories too; when engaging with my works, audiences have shared memories of their own grandparents, and their own family histories of migration. I’m keen to nurture these spaces of conversation and exchange.

LM: Of course, and such exchanges can help us understand these shared experiences in a more collective sense. You’ve described yourself in the past as a ‘memory collector’, how do you understand this role in relation to your practice?

AA: We are constantly making, gathering and transmitting memories through our bodies so yes, I perceive myself as a memory collector. In my performance Transitory Body: The Memory Collector (2020 - ongoing), I invited viewers to stamp a date on my body that represented a moment of dissection, division, partition or separation they experienced. They were then asked to whisper that memory into my ear and in return, I whispered one of mine to them. Through this exchange, a metaphorical migration of memory took place between our bodies. In other works, I use staged photography and mise-en-scène to recreate memories which I access through the body, sometimes by wearing the same clothes as the characters I am referring to, or by embodying their gestures and actions. In these moments, the act of becoming is central to my process; it allows me to inhabit, reinterpret and reanimate memories through performative embodiment.

This performance work has helped me realise how profoundly the body operates as a repository of memory. It has encouraged me to question the conventional notion that memory resides solely in the mind. Now, I’m exploring how memory is embedded in the body, how it can be accessed, performed and re-enacted through gesture, touch and presence. It has also helped me create space for forms of memory that are often institutionally overlooked or dismissed as insignificant.

LM: I’m intrigued and excited to see how these ideas and memories continue to surface in your work moving forwards. Thank you Arpita.

Arpita Akhanda is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice explores the relationship between present experiences and historical trauma, particularly the legacy of displacement during the partition of India. Working across paper weaving, performance, installation, drawing and video, she views the body as a "memory collector," where post-memorial experiences are mediated through recreation and projection.

Three of Akhanda’s intricately hand-woven paper works from the series A Veil of Memories feature in the exhibition. Weaving together layers of maps and images of her grandparents, Akhanda’s work grapples with intergenerational memories, family archives and the cartography of colonialism.

10 Oct 2025 – 21 Mar 2026

A free exhibition examining political dissent and erasure through the idea of collage

Banner image: Arpita Akhanda, A Veil of Memories IV [detail], 2023. © and courtesy the artist and Emami Art Gallery.

Images on page: 1) Arpita Akhanda, A Veil of Memories IV, 2023. © and courtesy the artist and Emami Art Gallery. 2) Arpita Akhanda, A Veil of Memories III, 2023. © and courtesy the artist and Emami Art Gallery. 3) Arpita Akhanda, Hath-Pakha, 2023 - ongoing. © and courtesy the artist. Image credit Jan Van Eyck Academie. 4-6) Arpita Akhanda, documentation from Transitory Body: The Memory Collector, 2020. © and courtesy of the artist. Photo documentation by Piramal Art Residency. 7) Image of Arpita Akhanda courtesy Sovereign Art Foundation. 8) Sabrina Tirvengadum and Mark Allred, Family [detail], 2023. © and courtesy the artists.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.