Thato Toeba is an artist and lawyer who uses collage to interrogate history – making visible those who have been othered within visual archives.

Below, the artist speaks with Autograph’s Senior Curator, Bindi Vora, about their newly commissioned work which features in I Still Dream of Lost Vocabularies, Autograph’s current exhibition examining political dissent and erasure through the idea of collage and constructed imagery. They discuss methods of making that embrace contradiction, to address the legacies of colonisation in Southern Africa.

Bindi Vora (BV): Can you tell me about yourself and the roles you hold as an artist and lawyer? How did art become a tool for you to create visual dialogues that merge law, rights and community together?

Thato Toeba (TT): I studied law at the National University of Lesotho (NUL), and my mother was also at the university at the same time, teaching and doing research. She is a demographer and sociologist and does a lot of empirical research for development programs like the World Bank. Sometimes, she would invite me and my siblings to be research assistants in her projects, giving us insight into life in relation to politics. So I had quite a unique university experience, because I didn’t just study law in the context of the classroom and within the prescribed syllabus; I also understood law as sociological, as something that shaped everyday life and politics in the communities around me.

The year before I graduated, I bought a camera. I started photographing weddings, graduations and everyday stuff like that. In a way this shaped my way of seeing and desire to see. I later moved to Cape Town for my PhD at the University of the Western Cape. I arrived in Cape Town as #rhodesmustfall and later #feesmustfall started. #Rhodesmustfall protested the monumentalisation of colonialist Cecil Rhodes in the University of Cape Town and the continued coloniality of the university curriculum, whilst #feesmustfall built on the former while also protesting the increase of fees in public universities in South Africa. Coming from Lesotho, where discontent with state systems is usually expressed passively, #feesmustfall introduced a language of volatility that radicalised my thinking on global politico-economic arrangements.

It was also in Cape Town that I went to a gallery for the first time at the age of 25 and began connecting curatorial vision with artworks that reflected the broader issues in our society. I began to understand art as a very serious and fast medium through which I could communicate ideas and thoughts. Everything in me was rejecting my education and all the ‘truths’ that I was being taught. And then the pandemic arrived, and in some ways it felt quite miraculous to me; I had wished something would happen that could interrupt the rapid pace of capitalism and its demands so I could catch my breath. And then it happened.

I was obsessed with the idea of power and knowledge: what does it mean to know something and create knowledge? When I think about images – and particularly documentary photographs – they can be read as law as they propose objectivity. Law often enables people to accept things that they’d otherwise consider atrocious because it creates a sense of objectivity.

BV: Throughout our conversations, I’ve always been struck by how you engage with contradiction – not just thematically, but materially – using it as a catalyst to explore the need for a decolonial approach to image-making. Your use of collage, with its layering and fragmentation, feels especially powerful in this context. Could you speak more about how collage supports or reflects these ideas in your work?

TT: When I started making art it was during the pandemic: I didn’t have access to public spaces or elaborate ways of staging photographs but I did have access to magazines. It forced me to think about the images that exist in the world and how they function and speak to a recurrent cycle of events. Even now, when I open a page from a 1987 copy of National Geographic, I will find images that feel similar to what I’m seeing today, for example in Gaza.

Even outside of the pandemic, I would struggle with access because African archives are in Europe, since colonial Europe had access to the camera and access to the subject. So if I want to engage with that era or that time, I have to engage with other people's images as opposed to my own.

South Africa is very interesting in this regard because there were a lot of skilled white photographers with access to black spaces. They were active in the Apartheid era and still remain authoritative figures in the visual landscape of South Africa today. Photographers like David Goldblatt, Pieter Hugo, Jodie Bieber make beautiful images of black life in my view that give us historical archival material with which we can reimagine future possibilities. Their work speaks about the issues that have long affected the country and have been so useful in framing this kind of collective visual memory we have that is difficult to grapple with.

Zwelethu Mthethwa, a South African photographer who was convicted of murder, was quite a prominent image maker – he went to the art school in Cape Town, at a time when the Michaelis School of Fine Art was not accepting black people into its classes. Parliament had to pass a special order for him to attend, a change which was only possible because he came from an influential background. After his conviction his work became controversial and I kept thinking about what that meant for the subjects he photographed and these spaces he had been invited into. Are they now inaccessible? It kept bringing me back to who now owns these stories. Images are very political in the way that they're made – they’re not neutral. Therefore, I want to revisit images and sit with those mechanics. So my practice in collage helps me to create more possibilities and facilitate a conversation between images.

BV: Over the last few months, we’ve been in dialogue about a new work you have developed for the exhibition I Still Dream of Lost Vocabularies, co-commissioned by Autograph and the V&A. This piece delves into the archive of Horace Nicholls, a photographer featured prominently in the Royal Photographic Society collection held at the V&A. In what ways did these archival images shape your visual language around labour, visibility and the historical presence of black bodies in Southern Africa’s extractive economies?

TT: Interestingly, when we began to talk about the exhibition at Autograph, we circled back to a work I made in 2017 called Man on Fire. This piece, which is presented in the show as a large-scale wallpaper, references the story of Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave, a Mozambican man who was burned to death during a wave of xenophobic violence in Johannesburg in 2008. So when I talk about these histories, they aren’t just about the 1900s, 1950s or something that happened in the past, it's something that is happening today, yesterday and continues. This is where Horace Nicholls is speaking to us from. I wanted to juxtapose or contradict Nicholls’ images with those of Johannesburg as a shared but very charged space. The archives are really working hard at mainlining a particular kind of acquiescence from us which I feel needs to be interrupted, even if just to understand the present.

When I saw the images that Nicholls produced, I realised that the question of where the black people were was soon answered; they were likely underground, working in the mines. I read an academic article from 1915 that spoke about the state of mining in Rand and it was very objective and sanitised. Likewise, when I see Nicholls’ images, they show a very one-dimensional perspective, there’s no violence or trauma for black people. Everyone appears to live together in a utopian world.

It was also interesting to revisit the history of the Boer War - a conflict between the British Empire and the Dutch Boer republics - which Nicholls documented. We studied the Boer War in school and discussed it at university but there were many parts of it that I was not aware of. Now living in the Netherlands where the Dutch are and to be making this commission in London, I felt very present across these countries. Our language, culture and families are irrevocably intertwined.

BV: The work you have been developing for the commission is formed of two parts – I am curious about this idea of duality and separation, can you speak more on that?

TT: When I was practicing law, people often used to talk about inherited law or colonial traditions with fondness, revering our relationship with the British. Lesotho’s Administration of Estates Proclamation of 1935 (which was repealed in 2024) asked people to abandon their customary life and adopt a European way of life, in order to be able to share inheritance and make wills; it promoted access to 'modernity' through Europeanisation, even if at cost to one’s self and one’s traditions. This 'modern' attitude might be demonstrated by having a white wedding rather than a customary wedding. When I looked through these images in the V&A’s archive, the recurring emphasis on 'white' traditions became apparent – a white wedding, communion, christenings, the use of lace etc – the images reflected a white culture both in tradition and in aesthetic.

So in the new work, I wanted to show two intertwining scenarios revolving around two central characters, a 'groom' and a 'bride', to subvert the development of the institutions which sought to make Africa look unavoidably European. I wanted to think about ways of existing in plurality as opposed to within a set of prescribed boundaries. So the groom for example, is a Zulu warrior but they’re also a rickshaw puller. This mode of transport was introduced to South Africa in the 19th century and became a key part of the country's transportation system and a tourist attraction. Likewise, I’ve tried not to ascribe a sexuality to the couple getting married – people always try to seek something that they recognise, but I want to disturb and challenge that to make people look more closely. So I think these characters are doing poetic work as well as working in a more literal and narrative way.

BV: And this act of resistance also extends to the clothing of the figures, is that right?

TT: Yes, the suits that the individuals are wearing also hold particular meaning; one is based on the suit that Nelson Mandela wore the day he was released from prison. The other suit references Marvin Gaye. Gaye was murdered by his father. He had always had a difficult relationship with his father but the ambiguity surrounding both of their sexualities is said to have contributed to the altercation that led to Gaye’s death.

BV: The structure of the work has a very particular form: although each piece is quite abstract in shape, you can decipher partial silhouettes of a horse and of a figure. Could you talk about that.

TT: The work is called The Earth Underneath a Pulverised Horse and throughout the process of making this work I frequently came back to the question: where are the black people? Horses also cropped up frequently in Nicholls’ archive. Through my research, I discovered that 300,000 horses are estimated to have died during the Boer War. These silhouette forms are intended to focus the viewer’s gaze on the invisibility of these figures and stories in the archive. So I’ve been thinking about the idea of the space in between spaces, and what it means to focus on that. When working with montage you cut in and out of images, and the most important thing for most people is the element you cut out – the image that you want to isolate and pull out, but in this moment, the space that becomes more visible stood as a metaphor for the earth beneath the horse, because under the horse and ground are black people digging.

BV: In some ways, reclaiming histories that have been disassembled, erased or perhaps marginalised is where the tensions of collage come into play. Collage often brings together fragments that may not naturally belong – allowing for dissonance, rupture and unexpected harmony. How do you think about the act of assembling these fragments in relation to memory and resistance? Is collage, for you, a way of re-authoring histories that have been disassembled or erased?

TT: I still can’t define exactly what collage is for me but certainly a part of it is that it provides a language and a way of world building. Images can function as language and I find when you put one image against the other, you end up constructing simple sentences. Photographs feel to me, as a material, as maybe plaster or paint feel to another artist.

Thato Toeba (b. 1990, Maseru, Lesotho) is an artist, lawyer, and social sciences researcher who works with mixed-media photomontage and assemblage. Their practice draws on historical archives and architectural space to explore themes of power, the legacy of Empire, and its ongoing influence on the collective spirit of the global South.

Toeba holds an LLM from Humboldt University, Berlin (2015), they were an artist-in-residence at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam (2023-25). Their work has been exhibited at Mount Nelson (South Africa), Morija Museum (Maseru), Kunstinstitut Melly (The Netherlands), and other venues. In 2025 they were awarded the 15th FNB Art Prize (Soth Africa). Their works are held in public collections including, Autograph, London and V&A, London.

10 Oct 2025 – 21 Mar 2026

A free exhibition examining political dissent and erasure through the idea of collage

Banner image: Thato Toeba, The Earth Underneath a Pulverised Horse, I and II [detail], 2025. Co-commissioned by Autograph, London and the V&A Parasol Foundation Women in Photography curatorial project. © and courtesy the artist.

Images on page: 1) Thato Toeba, Ka ha ka ka mona ha se ka mantloaneng, 2022. © and courtesy the artist. 2) Thato Toeba, Man on Fire, 2017. © and courtesy the artist. 3) Thato Toeba, The Earth Underneath a Pulverised Horse I and II, 2025. Co-commissioned by Autograph, London and the V&A Parasol Foundation Women in Photography curatorial project. © and courtesy the artist. 4) Thato Toeba, The Earth Underneath a Pulverised Horse II [detail], 2025. Co-commissioned by Autograph, London and the V&A Parasol Foundation Women in Photography curatorial project. © and courtesy the artist.

About the artist: Image courtesy of the artist.

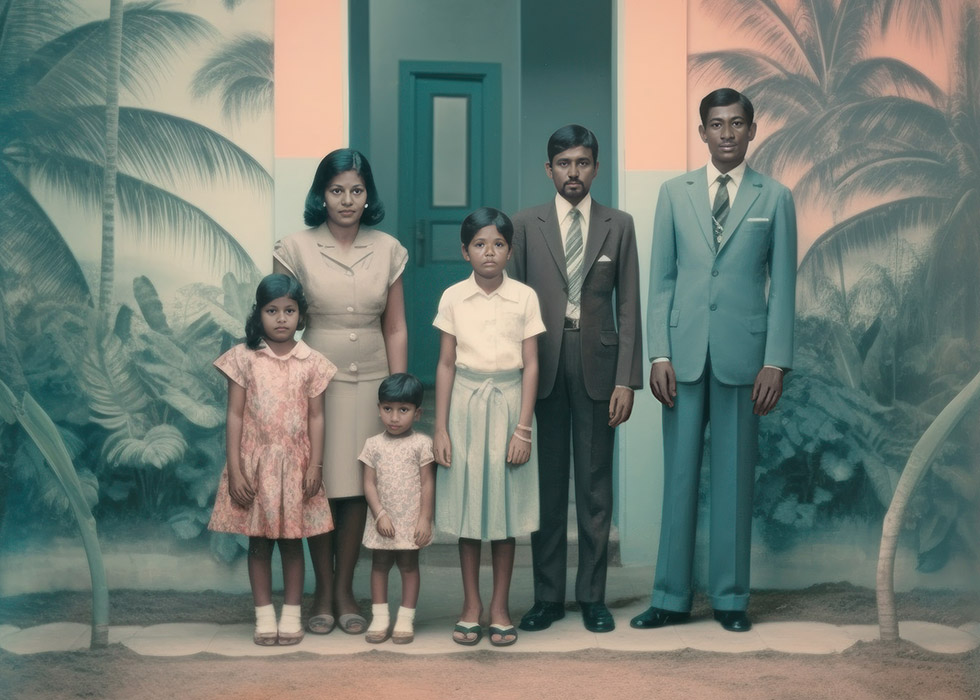

Exhibition: Sabrina Tirvengadum and Mark Allred, Family [detail], 2023. © and courtesy the artists.

Autograph is a space to see things differently. Since 1988, we have championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice, sharing how photographs reflect lived experiences and shape our understanding of ourselves and others.